Hospitals and clinics will have the first opportunity to recognize and initiate a response to a bioterrorism-related outbreak. Therefore, overall disaster plans must address the issue. Individual facilities should determine the extent of their bioterrorism readiness, which may range from notification of local emergency networks (i.e., calling 911) and transfer of affected patients to appropriate acute care facilities, to activation of large, comprehensive communication and management networks. This course will attempt to briefly summarize the characteristics, treatment, and prophylaxis of potential bioterror agents. The role of the medical professional will be outlined, and the appropriate "do's and don'ts" will be discussed. Reporting procedures and disaster plans will also be reviewed.

- INTRODUCTION

- UNDERSTANDING AND RESPONDING TO BIOTERRORISM

- TYPES OF AGENTS

- BACTERIAL AGENTS

- VIRUSES

- TOXINS

- DETECTING AND MANAGING A BIOLOGIC ATTACK

- APIC BIOTERRORISM READINESS PLAN

- CONSIDERATIONS FOR NON-ENGLISH-PROFICIENT PATIENTS

- RESOURCES

- CONCLUSION

- Works Cited

- Evidence-Based Practice Recommendations Citations

This introductory course is designed for psychologists, all of whom are expected to respond in the case of a bioterrorist event.

Continuing Education (CE) credits for psychologists are provided through the co-sponsorship of the American Psychological Association (APA) Office of Continuing Education in Psychology (CEP). The APA CEP Office maintains responsibility for the content of the programs.

The purpose of this course is to address the various components of a bioterrorism attack and the appropriate responses required of clinical care providers, public health professionals, and healthcare facilities.

Upon completion of this course, you should be able to:

- Discuss the role of the medical professional in the event of a bioterrorism attack.

- Reflect on the history of bioterrorism.

- Identify the CDC categories of possible bioterror agents and diseases.

- Explain the types of dispersion.

- Compare available bacterial agents, their diagnosis, and treatment procedures, and how they could be used during a bioterrorist attack.

- Analyze viral agents with the potential for bioterrorist use, including smallpox and viral hemorrhagic fevers.

- Evaluate biologic toxins and how they might be used in biowarfare.

- Apply a disaster plan for acts of terrorism that involve biologic weapons, including considerations for non-English-proficient populations.

Carol Shenold, RN, ICP, graduated from St. Paul’s Nursing School, Dallas, Texas, achieving her diploma in nursing. Over the past thirty years she has worked in hospital nursing in various states in the areas of obstetrics, orthopedics, intensive care, surgery and general medicine.

Mrs. Shenold served as the Continuum of Care Manager for Vencor Oklahoma City, coordinating quality review, utilization review, Case Management, Infection Control, and Quality Management. During that time, the hospital achieved Accreditation with Commendation with the Joint Commission, with a score of 100.

Mrs. Shenold was previously the Infection Control Nurse for Deaconess Hospital, a 300-bed acute care facility in Oklahoma City. She is an active member of the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC). She worked for the Oklahoma Foundation for Medical Quality for six years.

Elizabeth T. Murane, PHN, BSN, MA, received her Bachelor’s degree in nursing from the Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing, Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio and a Master of Arts in Nursing Education from Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, New York.

Her nursing experience includes hospital nursing on pediatric, medical, and surgical units. She lived for 15 years in a village in Eastern Papua New Guinea providing medical and linguistic/literacy services for the villagers. She was a public health nurse for a year with the Brooklyn, New York Health Department and 20 years with the Shasta County Public Health Department in Redding, California. As a public health nursing director, she developed response plans for environmental and health issue disasters for both Shasta County and adjacent Tehama County Public Health Departments.

Contributing faculty, Carol Shenold, RN, ICP, has disclosed no relevant financial relationship with any product manufacturer or service provider mentioned.

Contributing faculty, Elizabeth T. Murane, PHN, BSN, MA, has disclosed no relevant financial relationship with any product manufacturer or service provider mentioned.

Margaret Donohue, PhD

The division planner has disclosed no relevant financial relationship with any product manufacturer or service provider mentioned.

Sarah Campbell

The Director of Development and Academic Affairs has disclosed no relevant financial relationship with any product manufacturer or service provider mentioned.

The purpose of NetCE is to provide challenging curricula to assist healthcare professionals to raise their levels of expertise while fulfilling their continuing education requirements, thereby improving the quality of healthcare.

Our contributing faculty members have taken care to ensure that the information and recommendations are accurate and compatible with the standards generally accepted at the time of publication. The publisher disclaims any liability, loss or damage incurred as a consequence, directly or indirectly, of the use and application of any of the contents. Participants are cautioned about the potential risk of using limited knowledge when integrating new techniques into practice.

It is the policy of NetCE not to accept commercial support. Furthermore, commercial interests are prohibited from distributing or providing access to this activity to learners.

Supported browsers for Windows include Microsoft Internet Explorer 9.0 and up, Mozilla Firefox 3.0 and up, Opera 9.0 and up, and Google Chrome. Supported browsers for Macintosh include Safari, Mozilla Firefox 3.0 and up, Opera 9.0 and up, and Google Chrome. Other operating systems and browsers that include complete implementations of ECMAScript edition 3 and CSS 2.0 may work, but are not supported. Supported browsers must utilize the TLS encryption protocol v1.1 or v1.2 in order to connect to pages that require a secured HTTPS connection. TLS v1.0 is not supported.

The role of implicit biases on healthcare outcomes has become a concern, as there is some evidence that implicit biases contribute to health disparities, professionals' attitudes toward and interactions with patients, quality of care, diagnoses, and treatment decisions. This may produce differences in help-seeking, diagnoses, and ultimately treatments and interventions. Implicit biases may also unwittingly produce professional behaviors, attitudes, and interactions that reduce patients' trust and comfort with their provider, leading to earlier termination of visits and/or reduced adherence and follow-up. Disadvantaged groups are marginalized in the healthcare system and vulnerable on multiple levels; health professionals' implicit biases can further exacerbate these existing disadvantages.

Interventions or strategies designed to reduce implicit bias may be categorized as change-based or control-based. Change-based interventions focus on reducing or changing cognitive associations underlying implicit biases. These interventions might include challenging stereotypes. Conversely, control-based interventions involve reducing the effects of the implicit bias on the individual's behaviors. These strategies include increasing awareness of biased thoughts and responses. The two types of interventions are not mutually exclusive and may be used synergistically.

#61764: Bioterrorism: An Update for Healthcare Professionals

The United States government expects healthcare professionals to be on the front line of defense and treatment in the event of a bioterrorism attack in our country. This includes most medical personnel, but especially physicians, nurses, physician assistants, mental health professionals, and dentists. Increasing awareness and knowledge of possible bioterrorism agents and attacks will increase healthcare professionals' ability to respond properly.

Hospitals and clinics will have the first opportunity to recognize and initiate a response to a bioterrorism-related outbreak. Therefore, overall disaster plans must address the issue. Individual facilities should determine the extent of their bioterrorism readiness, which may range from notification of local emergency networks (i.e., calling 911) and transfer of affected patients to appropriate acute care facilities, to activation of large, comprehensive communication and management networks [1].

This course will attempt to briefly summarize the characteristics, treatment, and prophylaxis of potential bioterror agents. The role of the medical professional will be outlined, and the appropriate "do's and don'ts" will be discussed. Reporting procedures and disaster plans will also be reviewed.

There are many definitions of bioterrorism. Most are similar to the definition provided by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security: Bioterrorism is the use of biological agents (organisms or toxins) that can sicken, disable, or kill people, livestock, or crops [2].

What is the role of the practicing medical professional in the event of a bioterrorism attack and what is the expected response? This may be broken down into three simple steps: Identify, Report, and Refer [3].

Be aware of the signs and symptoms of a bioterror agent

Know the appropriate tests to request

Have an awareness of possible differential diagnoses

Be able to contact the appropriate agencies

Initiate the preprogrammed response by public and government agencies

Be able to refer victims of possible bioterror to bioterrorism experts or specialists

Refer any media requests to these individuals as well

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and other public health agencies recommend being extra vigilant with patients, sharing information with them, allaying their fears, and helping them to understand the limits of the bioterror agents. Conversely, these organizations strongly advise against:

Prescribing antibiotics inappropriately

Stockpiling antibiotics

Recommending gas masks

Unnecessarily alarming patients or peers

It is important to remember that no single antibiotic will protect against all potential bacterial agents. The duration of protection from antibiotics is short. Indiscriminate use will waste supplies, induce drug resistance, and may lead to adverse effects. In addition, the organism used in an attack may have been engineered to be resistant to the commonly prescribed antibiotics [3].

Though not a new threat, the possibility of a biologic warfare attack on the United States has received markedly increased attention as a result of several world events, including the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks by al-Qaeda and the 2001 anthrax letter attacks (presumably by an American bioweapons researcher). In decades past, medical defense against biologic warfare was an area of study for military healthcare providers and did not readily apply to the day-to-day scope of caring for patients in peacetime. However, because the threat of biologic attacks against both soldiers and civilians enjoys a substantive existence today, education regarding prevention and treatment of biologic warfare casualties is indispensable.

The most successful bioterrorist attack in the United States before 2001 occurred in Oregon in 1984, when members of the Rajneesh commune attempted to influence the outcome of an election by infecting the salad bars of 10 restaurants with Salmonella spp. bacteria. They believed that if the local citizens were inflicted with diarrhea, they would not be able to vote. More than 750 people were sickened by the attack, but if this had been done with volatized anthrax spores, there could have been hundreds of fatalities [4,5]. The lead medical investigator admitted that public health officials were unprepared to deal with an attack of greater magnitude.

General antiterrorism training efforts intensified following the New York City World Trade Center bombing in 1993. The Tokyo subway sarin nerve agent release and Oklahoma City federal building bombing, both occurring in 1995, stimulated an additional increase in awareness of bioterrorism. In November 1997, Secretary of Defense William Cohen announced that all U.S. military troops would be immunized against anthrax as a precaution [6]. Additionally, the disclosure that a sophisticated offensive biologic warfare program existed in the former Soviet Union along with information obtained after the 2001 attacks on New York and Washington, D.C., reinforced the need for increased training and education.

The need for education on the subject of bioterrorism is evident. Preparation for such an event must include knowledge of the potential biologic agents with emphasis on their diagnosis, treatment, and management.

The CDC has defined three categories of possible bioterror agents and diseases. Agents are categorized according to their priority as risks to national security [7].

These are high-priority agents, including organisms that pose a risk to national security because they:

Can be easily disseminated or transmitted from person to person

Result in high mortality rates and have the potential for major public health impact

Might cause public panic and social disruption

Require special action for public health preparedness

The second highest priority agents include those that:

Are moderately easy to disseminate

Result in moderate morbidity rates and low mortality rates

Require specific enhancements of CDC's diagnostic capacity and enhanced disease surveillance

Brucellosis (Brucella species)

Epsilon toxin of Clostridium perfringens

Food safety threats (e.g., Salmonella species, Escherichia coli O157:H7, Shigella)

Glanders (Burkholderia mallei)

Melioidosis (Burkholderia pseudomallei)

Psittacosis (Chlamydia psittaci)

Q fever (Coxiella burnetii)

Ricin toxin from Ricinus communis (castor beans)

Staphylococcal enterotoxin B

Typhus fever (Rickettsia prowazekii)

Viral encephalitis

Alphaviruses (e.g., eastern equine encephalitis)

Water safety threats (e.g., Vibrio cholerae, Cryptosporidium parvum)

The third highest priority agents include emerging pathogens that could be engineered for mass dissemination in the future because of:

Availability

Ease of production and dissemination

Potential for high morbidity and mortality rates and major health impact

Category C agents are generally emerging infectious diseases, such as hantaviruses or Nipah virus [7].

Any disease that is contagious would be worrisome in our highly mobile society because people travel every day to many regions of the country and the world. If infected in an attack, a victim might fly from city to city or country to country before he/she becomes symptomatic, spreading the infecting agent at an alarming rate. However, this course will focus primarily on those agents deemed highest priority (Category A) by the CDC. Information pertaining to chemical agents will also be provided.

While the wild forms of the various bioterrorism pathogens are frightening and available, the threat of genetically engineered infectious agents is also a consideration. For example, it is known that researchers in Moscow created a recombinant strain of anthrax, raising the possibility that the current vaccine would be ineffective. With the constant advances in bioengineering, it is inevitable that biologic weapons will be created that are resistant to current postexposure treatments and vaccines [8].

Despite the very different properties of bacteria, viruses, and toxins, most biologic and chemical agents that can be used as weapons share some common characteristics. The most important characteristic is the ability of the agent to be dispersed in aerosols, with a particle size of 1–5 microns. These particles can remain suspended (in certain weather conditions) for hours and, if inhaled, will penetrate the distal bronchioles and terminal alveoli of victims. Particles larger than 5 microns would tend to be filtered out in the upper airway [9]. An indoor or domed stadium is a high-risk potential target for aerosolized biologic or chemical weapon attack.

Many of these agents may also be dispersed by contamination of foodstuffs, as was the case with the 1984 Rajneesh Salmonella attacks, although the effect is localized. It is estimated that less than 1 gram of botulinum toxin could poison 100,000 individuals if added to the commercial milk supply; nearly 600,000 could be poisoned with 10 grams [10]. Parasites (e.g., tapeworm eggs) could presumably be placed into a salad bar, salsa bar, or drinking water dispensers, and symptoms would not be seen until weeks or years after becoming infected [11]. This type of bioterrorist attack could be carried out for many months without being detected. Even after presentation of symptoms, diagnosis may not be rapid because many healthcare professionals are unfamiliar with tapeworm infections [11].

Waterborne dispersion is also a concern; however, the threat of harming large numbers of people by dispersing biologic or chemical agents into reservoirs is often mitigated by water treatment. Nonetheless, there have been successful bioterrorist attacks on drinking water supplies. One such incident occurred in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1990, when nine individuals in the same apartment complex were infected with Giardia[11]. The apartment complex had an unsecured water supply, which was purposefully contaminated with feces. A bioterrorist might tap into and contaminate a large building's water supply, which is unlikely to undergo additional purification.

Naturally occurring outbreaks, such as the 1999 New York County Fair E. coli and Campylobacter well-water outbreak (900 sickened and 2 dead) and the 1993 Milwaukee Cryptosporidium parvum outbreak (403,000 affected), further exemplify the susceptibility of drinking water to contamination and bioterrorism [11]. Some agents, such as anthrax, are resistant to routine water treatment processes, and the Milwaukee outbreak occurred despite filtration and chlorination [12]. Public pools, recreational water parks, and interactive fountains have been the source of several outbreaks of naturally occurring infections, sickening almost half of attendees in some cases [11]. These systems are particularly vulnerable to bioterrorist attack.

Bacterial agents are among the most probable sources of bioterror and include anthrax, brucellosis, plague, tularemia, and Q fever. They are generally easily accessible and fairly simple to spread. Bacteria can cause diseases in humans and animals by two possible means: by invasion of tissues or by production of toxins that cause a pathologic response. In many cases, pathogenic bacteria possess both properties. Fortunately, this group of agents often responds to specific therapy with antibiotics. The following sections will examine the more common bacterial agents in detail.

Anthrax is a zoonotic disease (an animal disease transmitted to humans) that is transmissible to humans through handling or consumption of contaminated animal products. The CDC considers Bacillus anthracis, the bacteria that causes anthrax, to be one of the biological agents most likely to be used in the event of a bioterrorist attack [13]. There are several reasons for this. The anthrax spores are easily found in nature, can be produced in the laboratory, and are stable for long periods of time. B. anthracis is easy to cultivate, and spore production is readily induced. The spores are highly resistant to sunlight, heat, and disinfectants. Anthrax spores can be released quietly and in many forms (e.g., powders, sprays, food, water) without being seen, smelled, or tasted. These are very desirable properties when choosing a bacterial weapon.

Anthrax has been used as a weapon before. Anthrax spores were actively experimented with as possible weapons by the United States in the 1950s and 1960s, before the military program was terminated. At least 17 nations are believed to have had offensive biologic weapons programs, but it is unclear how many were working with anthrax. In August 1991, Iraq admitted to a United Nations inspection team that it had performed research on the offensive use of B. anthracis prior to the Persian Gulf War of 1991 and, in 1995, also admitted to actively producing and testing anthrax as a bioweapon [9,14]. In 2001, powered anthrax spores were deliberately put into letters that were then mailed through the United States postal system. Twenty-two persons, including 12 mail handlers, got anthrax and 5 of the 22 died [13].

Anthrax can be produced in either a wet or dried form and stabilized for use as a weapon. It can be delivered as an aerosol cloud either from a line source, such as an aircraft, or as a point source from a spray device. If used as a weapon, an anthrax aerosol would be odorless and invisible following release and would have the potential to travel many kilometers before dissipating. Evidence suggests that following an outdoor aerosol release, persons indoors could be at as high a risk for exposure as those who are outdoors [15].

Four forms of anthrax occur in humans, with manifestations depending on how the organism is contacted. The diseases are distinct; however, infection with one form presents a risk for contracting the others.

Cutaneous Anthrax

Cutaneous anthrax is the most common naturally occurring form, with an estimated 2,000 human cases reported annually worldwide; however, it is extremely rare in the United States (0 to 2 cases per year) [16,17]. It also is considered to be the least dangerous. The disease typically follows exposure to anthrax-infected animals. Cutaneous infections occur when the bacterium or spores enter a cut or abrasion on the skin, such as when handling contaminated wool, hides, or leather.

Gastrointestinal (GI) Anthrax

Gastrointestinal (GI) anthrax is not commonly seen; however, outbreaks have occurred in Africa and Asia [17]. GI anthrax follows the ingestion of insufficiently cooked contaminated meat or tainted liquids. Officials believe it is unlikely that gastrointestinal anthrax would be used as a bioterror agent because a very high infective dose is required [11].

Inhalation Anthrax

Inhalation anthrax is the most deadly form of the disease, but it occurs less frequently as a naturally occurring disease than the cutaneous or GI forms. However, the dissemination of spores could cause widespread disease, and therefore, this is the most likely form of anthrax to be used as a biologic weapon. As noted, it has been weaponized by several countries because it is easy to cultivate, the spores are resistant to heat and disinfection, and it can be produced in massive amounts relatively inexpensively. Prior to the cases in 2001, inhalation anthrax had not been reported in the United States since 1976 [15,17]. This makes even a single case a cause for alarm today.

Injection Anthrax

Injection anthrax was recently identified in heroin-injecting drug users in northern Europe, but to date, no cases have been reported in the United States. The symptoms of injection anthrax are similar to those of the cutaneous form, but there may also be infection deep beneath the skin or in the muscle where the drug was injected. Injection anthrax spreads through the body quickly and is more difficult to recognize and treat than cutaneous or inhalation forms. Cases of injection anthrax typically develop within one to four days of exposure and more than 25% of individuals with confirmed cases die [16,18].

The first evidence of a clandestine release of anthrax as a biologic weapon would most likely be the sudden appearance of a large number of patients in a localized area, with the acute onset of a flu-like illness. A case fatality rate of 80% or more, with nearly half of all deaths occurring within 24 to 48 hours, is highly likely to be anthrax or pneumonic plague [15,17]. (Following the small-scale 2001 anthrax attacks, the case fatality rate was 45% [17].)

The initial symptoms are often followed by a short period of improvement [15]. Following this, there is an abrupt development of severe respiratory distress with dyspnea, diaphoresis, stridor, and cyanosis. Shock and death usually occur within 24 to 36 hours after the onset of respiratory distress. In later stages, mortality approaches 90% despite aggressive treatment [15]. Physical findings can be nonspecific. The chest x-ray is usually disease-specific, revealing a widened mediastinum with pleural effusions, typically without infiltrates [19]. Thoracic trauma can have similar signs, but often with infiltrates [20]. A hemorrhagic mediastinitis often develops.

Subclinical or clinical meningitis should also be suspected in victims of all types of anthrax [21]. Meningeal involvement has been documented in 77% of nonhuman primate models, and hemorrhagic leptomeningitis and meningoencephalitis have been reported in roughly half of human inhalation anthrax cases, including the 2001 letter attacks [5,21].

The anthrax skin infection begins as a raised pruritic lesion or papule that resembles an insect bite. Within one to two days, the lesion develops into a fluid-filled vesicle, which ruptures to form a painless ulcer, 1–3 cm in diameter, with a necrotic area in the center [15,19]. Pronounced edema is often associated with the lesions because of the release of an edema-producing toxin by B. anthracis. The lymph nodes in the area may become involved and enlarged. The incubation period in humans is usually one to seven days but could be prolonged to almost two weeks [15,19]. To describe the lesion in more detail, picture a painless macular eruption that appears within two to five days, most commonly on an exposed portion of the body. The lesion progresses from a red macule to a pruritic papule, then to a single vesicle or ring of vesicles. This is followed by a depressed ulcer and finally a black necrotic eschar that falls off within 7 to 10 days. There is edema associated with the eschar but usually no permanent scarring of the affected area. The cutaneous form of anthrax progresses to systemic disease in 10% to 20% of the cases, with a fatality rate of up to 20% if untreated [15,19]. Laboratory tests of blood products are usually normal if the disease is not disseminated. The systemic symptoms of cutaneous anthrax infection include fever, headache, regional lymph node involvement, and myalgia [19].

The B. anthracis organism can be obtained for culture or gram stain; however, analysis beyond simple cultures should only be performed in a specialized laboratory environment, and specimens (e.g., blood, skin lesion exudates, pleural fluid) should be collected before starting antimicrobial therapy [22]. On gram stain, the organism can be recognized as a large, rod-shaped, gram-positive, spore-forming bacillus. More positive identification requires lysis by gamma phage and direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) analysis or most positively by immunohistochemical staining. There is an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test available but generally only at reference laboratories [22]. A negative culture does not rule out cutaneous anthrax, especially if obtained after antibiotics are started.

In 2014, the CDC published updated guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of anthrax [23]. These guidelines addressed best practices for management of patients with naturally occurring or bioterrorism-related anthrax in conventional medical settings. However, an aerosolized release of B. anthracis spores over densely populated areas could become a mass-casualty incident that overwhelms conventional resources. In order to prepare for this possibility, the government has stockpiled equipment and therapeutics (medical countermeasures) for anthrax prevention and treatment. In 2015, the CDC published an additional set of guidelines for intravenous antimicrobial and antitoxin use, diagnosis of anthrax meningitis, and management of complications in the setting of a mass-casualty incident [24].

Most B. anthracis strains are sensitive to a broad range of antibiotics. Penicillin, ciprofloxacin, or doxycycline is usually recommended for the treatment of anthrax, although penicillin alone is not used [19,25]. To be effective, treatment should be initiated early; if left untreated, the disease is highly fatal. Anthrax treatment regimens were updated in the years following the 2001 letter attacks, due to the high mortality rate (45%) despite aggressive treatment [21].

Immediate postexposure prophylaxis with ciprofloxacin 500 mg or doxycycline 100 mg orally, twice daily, is commonly recommended. Treatment should continue for 60 days. If individuals are unvaccinated, a three-dose series of anthrax vaccine adsorbed (AVA) should also be administered [23]. Levofloxacin is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for postexposure prophylaxis in patients 18 years of age and older, but it is recommended as a second-line agent only, with use dictated by other medical issues [21,23]. Though off label, moxifloxacin and clindamycin are recommended alternatives [23].

In 2013, a new antibiotic derived from a marine actinomycete, anthracimycin, was discovered [26]. Although it is not yet FDA-approved, the agent shows significant activity against B. anthracis, and it may have a place in the treatment of anthrax in the future.

For treatment of systemic forms of anthrax infection in adults (e.g., inhalation anthrax, GI anthrax, meningitis and bacteremia), an intravenous (IV) combination antimicrobial regimen is recommended for two to three weeks, followed by single-drug oral therapy for an additional six weeks to reduce the risk of clinical relapse [23,27]. Initial empiric treatment for anthrax when meningitis is suspected or cannot be ruled out should include three antimicrobial agents with activity against B. anthracis, including one or more drugs with bactericidal activity and one protein synthesis inhibitor to reduce exotoxin production. All should have good central nervous system (CNS) penetration. Based on efficacy studies, antimicrobial activity, and achievable CNS levels, the usual preferred regimen consists of a quinolone (ciprofloxacin) plus a carbapenem (meropenem) for bactericidal effect, combined with linezolid and administered for two to three weeks or until the patient is stable [23]. In cases in which linezolid is contraindicated or unavailable, clindamycin is an acceptable alternative.

If meningitis is ruled out, the initial IV regimen for systemic anthrax may be reduced to a single bactericidal agent (e.g., ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin) combined with a protein synthesis inhibitor (either linezolid or clindamycin). If the infecting strain is susceptible to penicillin, then penicillin G is considered equivalent to quinolone options for primary bactericidal therapy [23].

After combination parenteral therapy has been completed and the patient is clinically stable, treatment can be transitioned to single-drug oral therapy to complete a total 60-day course of treatment [23]. This prolonged maintenance phase of therapy is intended to treat surviving spores of B. anthracis in patients who may have sustained an inhalational exposure. Antimicrobial selection is the same as for postexposure prophylaxis—ciprofloxacin, 500 mg every 12 hours, or doxycycline, 100 mg every 12 hours.

Treatment for special groups, such as children and pregnant women, must be considered carefully. Fluoroquinolones are not generally recommended because of possible side effects involving the skeletal system. Balancing risks against the concerns regarding engineered antibiotic-resistant anthrax strains, the Working Group on Civilian Biodefense (Working Group) and the CDC recommend that ciprofloxacin be used in pregnant women and in children for first-line therapy and postexposure prophylaxis [15,25]. Doxycycline should not be started in pregnant women unless the patient is in the third trimester, but it may be administered to children [21]. Amoxicillin may be used in pediatric treatment if the anthrax strain is susceptible to penicillin. The recommended pediatric dose is amoxicillin 45 mg/kg/day in three divided doses given at exact eight-hour intervals [28]. Elderly patients should be assessed for potential drug interactions and comorbidities, and treatment should be adjusted accordingly [21]. In general, the cephalosporins are not useful in treating anthrax because the anthrax organism produces an enzyme that neutralizes them.

Supportive therapy for shock, fluid volume deficit, and airway management may also be needed. Early and aggressive pleural fluid drainage is recommended for all hospitalized inhalation anthrax patients [21]. Drainage protocols similar to those for empyema or complicated pneumonia should be followed and should significantly reduce mortality [21].

Treatment of cutaneous anthrax requires treatment with oral ciprofloxacin or doxycycline for 7 to 10 days, or IV ciprofloxacin or doxycycline for severe, naturally acquired cases [21]. Other fluoroquinolones or penicillin can be substituted as oral regimens for uncomplicated cutaneous anthrax if well monitored. Treatment for bioterrorism-related cutaneous anthrax cases requires a 60-day course of postexposure prophylaxis with the recommended antibiotics due to the possibility of aerosol exposure [21]. Cutaneous anthrax cases with lesions of the head or neck, extensive edema, or systemic involvement should also be treated using the recommended 60-day multidrug approach, as discussed for the treatment of severe disease.

Human-derived anthrax immune globulin (AIG) was used to successfully treat a naturally occurring inhalation anthrax case in Pennsylvania in 2006 [21]. In 2015, the FDA approved AIG for the treatment of inhalation anthrax [29]. Immune globulin administration may be considered in combination with appropriate antibiotics when multiple organ systems are involved or following lack of response to standard therapy.

Vaccination for anthrax can prevent the disease if given prior to contact with the bacillus. However, it can also be used postexposure to help minimize the patient's reaction to the organism. AVA is the only licensed human anthrax vaccine in the United States [17,30]. As of 2023, two different formulation of AVA (BioThrax and Cyfendus) are approved by the FDA. The approved pre-exposure prophylaxis schedule of BioThrax consists of five 0.5-mL injections administered intramuscularly (IM) in the deltoid region, at 0 and 4 weeks and 6, 12, and 18 months [17]. Individuals with contraindications to IM injections may receive the vaccine subcutaneously. (Routine subcutaneous pre-exposure vaccination with AVA is no longer recommended due to high incidence of adverse effects, approximately 6% for local inflammation and 2% to 3% for systemic symptoms.) The vaccine is approved only for healthy, nonpregnant adults, but may be considered during pregnancy when the benefits outweigh the risks [17,21]. As noted, a 60-day course of antibiotics is recommended for everyone potentially exposed to B. anthracis spores. Anthrax vaccine is also recommended for post-exposure prophylaxis in order to extend the duration of protection for a longer period of time.

AVA supplies may be insufficient to immunize an entire population potentially exposed following a wide-area aerosol attack, as in a major city. To address this possibility, the CDC has published guidelines for a risk-based approach to handling prioritization of AVA following an intentional release of B. anthracis spores [31]. The risk for inhalation anthrax following exposure to B. anthracis spores is best estimated by the degree of exposure, not by health status or age. In the aftermath of an aerosol attack, respiratory or inhalational exposure to B. anthracis spores may be immediate (primary aerosol) or delayed (secondary aerosols). Primary aerosols are particles dispersed into the air following the initial release, while secondary aerosols arise from later environmental disturbance and re-suspension of settled particles. The degree of exposure (hence the risk of inhalation anthrax) may be less from secondary than primary aerosols because re-aerosolization produces larger-diameter particles and lower airborne concentrations. The CDC recommendations specify that the degree of exposure to B. anthracis spores should determine prioritization of AVA vaccine usage. Highest priority should be given to any individual who was potentially exposed to primary aerosolization and therefore is at highest risk for inhalational anthrax. Secondary priority should be given to those with greatest risk from re-aerosolization (i.e., in the days and weeks after an event). Exposure risks for children and adults are judged to be indistinguishable based on present knowledge. The CDC guidance includes detailed vaccine priority risk tiers based on primary exposure, risk to responders and essential workers, occupational risk groups, and progressive distance from the central affected area [31].

Both BioThrax and Cyfendus are approved for postexposure vaccination. Cyfendus is given as two doses provided over 14 days, while the schedule of BioThrax consists of three injections of 0.5 mL of the vaccine administered subcutaneously [17]. After the first injection, the follow-up doses are given two and four weeks later. Despite the associated adverse reactions, subcutaneous AVA vaccination results in rapid anti-PA antibody production at much higher levels than the IM route [17].

There are no data to suggest patient-to-patient transmission of anthrax; therefore, only standard barrier isolation precautions are recommended for hospitalized patients with all forms of anthrax [9]. There is no need to immunize or provide prophylaxis to patient contacts unless a determination is made that they, like the patient, were exposed to the aerosol at the time of the attack.

Standard disinfectants used for hospital infection control are effective in cleaning surfaces contaminated with infected bodily fluids. In the setting of an announced alleged anthrax release, any person coming in direct physical contact with a substance thought to be anthrax should perform thorough washing with soap and water [15].

Proper burial or cremation of humans and animals that have died because of anthrax infection is essential to prevent further transmission of the disease. Serious consideration must be given to cremation. Embalming of bodies could be associated with special risks [15].

Plague is a word that brings visions of death and destruction. Indeed, the disease caused by the gram-negative bacillus Yersinia pestis has been responsible for millions of deaths throughout history. Of the three main types of plague, bubonic, septicemic, and pneumonic, the most likely source of bioterror would be pneumonic plague [32,33]. Two other less common forms of the disease, plague meningitis and plague pharyngitis, also occur [33]. Y. pestis occurs in nature and could be isolated and cultivated in a laboratory. An aerosol attack could cause multiple cases of the pneumonic form of plague followed by secondary spread to others via exhaled droplet nuclei, resulting in rapid propagation of disease.

Historically, plague represented disaster for Africa, Asia, and Europe [32,34]. At times, there were not enough people left alive after an outbreak to bury the dead. The cause of plague was unknown, and the outbreaks caused massive panic. It was believed by many that the disease was a form of punishment. Innocent people blamed for spreading plague found themselves persecuted by panicked masses. Even now, a suspected plague outbreak can incite mass panic [20,34].

Some speculate that the 14th century plague pandemic (the "Black Death") moved west out of Asia along with the advance of the Mongol Tartar army, which was recurrently affected by plague outbreaks [35]. In fact, during the 1346 Siege of Caffa, the Tartar invaders hurled plague-infected cadavers over the city walls using catapults. At the time, it was thought that the stench of the rotting bodies was enough to kill, but in actuality the bodies may have carried infected fleas that spread the disease [11]. Those who managed to escape Caffa fled to other Italian towns, where the plague flourished. Other scholars speculate that infected fleas were brought to Caffa along the Silk Road among trade goods (e.g., furs) or foodstuffs (e.g., rice) [11].

There is evidence that Japan investigated the use of Y. pestis as a biologic weapon during World War II [11]. They reportedly worked on a plan for attacking enemy troops with the organism by releasing plague-infected fleas [9]. In 1941, a Japanese plane was observed dropping grain and wadded cotton and paper over the business center in Changteh, China [11]. Roughly one week later many people began dying of plague. A similar incident occurred in 1940 in another Chinese city, where 99 individuals died of plague. Both towns were in nonendemic regions.

The United States worked with Y. pestis as a potential biowarfare agent in the 1950s and 1960s, before the biowarfare program was terminated [32]. American forces were accused of dropping insects on North Korea during the Korean War to cause a variety of infectious diseases; however, these claims have never been substantiated [11].

Humans may acquire plague from the bite of infected fleas, contact with or ingestion of contaminated tissue, inhalation of bacteria-laden droplets from humans or animals (particularly cats) infected with plague pneumonia, or from artificially generated aerosols [11]. Bubonic plague is the most common form of infection, resulting from the bacteria being taken up by the host macrophages in the lymph nodes [32]. The "bubo" is an inflamed, enlarged, and painful lymph node. From the infected lymph node, bacteria may multiply and become bloodborne, occasionally lodging in the lungs. Patients may progress from bubonic or septicemic plague to pneumonic plague if untreated [36].

When plague becomes pneumonic, direct person-to-person transmission via bacterial aerosolization becomes a real threat [36]. Progression of pneumonic plague is rapid and, if untreated, may lead to death in a few days [32]. Pneumonic plague is rare and requires close contact for transmission to occur, except in the case of weaponization. Prompt antibiotic treatment following early diagnosis is effective against all forms of plague infection [36]. If plague is suspected, local and state health departments should be notified immediately. If pneumonic signs are present, the patient should be isolated and placed on droplet precautions.

Few physicians in the United States have ever seen a case of pneumonic plague, although Y. pestis is distributed worldwide. Techniques for mass production and aerosolization are readily available. The fatality rate of primary pneumonic plague is high, with potential for secondary spread [32]. A biologic attack with plague is considered a serious threat. With sporadic cases likely to be missed or not attributed to a deliberate act, any suspected case of plague should be reported immediately by telephone to the local health department. A sudden appearance of many patients presenting with fever, cough, a fulminant course, and high fatality rate should raise suspicion for anthrax or plague. The tentative diagnosis of pneumonic plague is favored if the cough is accompanied by hemoptysis [37].

As noted, less common manifestations of plague include plague meningitis and plague pharyngitis [32]. Plague meningitis, resulting from spread of the bacilli into the meninges, is characterized by fever, nuchal rigidity, photophobia, and headache. Plague that primarily affects the pharynx is caused by inhalation or ingestion of Y. pestis and is generally recognized by the associated cervical lymphadenopathy [32].

The clinical presentation of bubonic plague is differentiated from other syndromes consisting of fever, malaise, headache, and chills by the presence of extremely painful lymph nodes [38]. The nodes involved may be axillary, inguinal, or cervical, with inguinal involvement being the most common. The nodes become fluctuant and tender and may necrose and drain. The bubo is often a discolored, necrotic mass [34]. Advanced cases of the disease may progress to secondary pneumonic or septicemic plague. The typical incubation period for bubonic plague is two to eight days [32]. A history of camping in an endemic area or of contact with infected animals (usually rodents) is a clue to the diagnosis [38].

Primary septicemic plague presents in the same general manner as other gram-negative bacterial septicemias. Like bubonic plague, there is usually a high fever, chills, headache, and malaise. Gastrointestinal disturbance may be present as well. In addition, there may be progression to septic shock with meningitis, coma, and coagulopathy. Secondary pneumonic plague may also develop. Laboratory tests may be required to differentiate it from other causes of gram-negative sepsis. A clue to the diagnosis of septicemic plague is the development of thrombosis in the acral vessels, resulting in gangrene of the fingers and toes [32]. Y. pestis is likely the only gram-negative bacterium that can cause extensive, fulminant pneumonia with bloody sputum [11].

Primary pneumonic plague has an incubation period of one to three days [34]. Patients present with a very high fever of acute onset, chest pain, myalgia, a cough that may be purulent or bloody, malaise, headache, and increased respiratory and heart rates. The pneumonia may progress rapidly to multiple organ failure and death [32,34]. Other clinical manifestations may include coagulopathy with acral cyanosis, petechiae, dyspnea, stridor, and, finally, respiratory failure. A chest x-ray after two to three days of incubation will reveal a patchy or consolidated bronchopneumonia. Unless appropriate antibiotics are administered within 24 hours of the onset of symptoms, the death rate approaches 100% [9].

The initial screening for plague is by microscopic analysis of stained samples from appropriate fluids, such as lymph node aspirate, blood, sputum, and/or cerebrospinal fluid. Specimens should be taken prior to initiation of antibiotic therapy [39]. Gram stain can show a characteristic gram-negative rod with a bipolar ("safety pin") appearance that is very suggestive of Y. pestis[39]. When Wayson staining is used, the organism shows up as a light blue bacillus with dark blue polar bodies in a pink background. The nonspecific finding of increased leukocytes with a left shift is usually present.

Isolation on culture media, biochemical testing, and phage lysis (for confirmation) may be performed [11]. Culture is slow and may appear negative at 24 hours. Reference laboratories may perform polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based assays and direct fluorescent antibody tests to detect the plague-specific Fraction 1 (F1) capsular antigen. A rapid diagnostic dipstick test, utilizing monoclonal antibodies to the F1 antigen, can provide results in as little as 15 minutes [11]. This test has proven useful in field trials in Madagascar, and two commercially available dipsticks demonstrated "diagnostic potential" in a 2011 study [40]. However, some virulent strains of Y. pestis, either natural or engineered, lack F1 protein capsules and would be undetected by these tests [41].

The Working Group on Civilian Biodefense developed recommendations for healthcare providers to follow in the event plague is used as a biologic weapon [32]. In 2021, on the basis of new developments, expert forum discussions, and other considerations, the CDC published changes to these recommendations, as follows [42]:

Simplified the guidelines to treatment and prophylaxis scenarios, similar to clinical guidelines for other biologic threats, to provide greater flexibility when responding to uncertain situations.

Added recommendations for treatment and prophylaxis of clinical forms of plague other than pneumonic, including bubonic, septicemic, pharyngeal, and meningeal.

Added recommendations for neonates and breastfeeding infants.

Listed ciprofloxacin as a first-line (preferred) agent for treatment of plague rather than an alternative option; more data are now available to support its use. Levofloxacin and moxifloxacin, which were not included in previous guidelines, are listed as first-line agents or alternatives for both treatment and prophylaxis.

Added several same-class alternatives to first-line fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, and tetracyclines to expand the repertoire of treatment and prophylaxis options to meet surge capacity, if needed.

Added the sulfonamide drug trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole as an alternative option for prophylaxis of plague.

Added recommendations for pre-exposure prophylaxis in addition to revising postexposure prophylaxis recommendations.

Clinical suspicion of plague should prompt immediate treatment of symptomatic patients with two distinct classes of antimicrobials, at least one of which is first-line, until sensitivity patterns of the infecting Y. pestis strain are known. While naturally occurring antimicrobial resistance is rare in Y. pestis, there is potential for engineered resistance as part of a bioterrorism release. Treating initially with two distinct classes of antimicrobials increases the likelihood that the patients will receive at least one effective agent [42]. FDA-approved antimicrobials for treatment and prophylaxis of plague include streptomycin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, and doxycycline. Although gentamicin, chloramphenicol, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole are not FDA approved for plague, they are considered to be effective based on clinical experience and animal data [42].

The aminoglycosides gentamicin and streptomycin, and the fluoroquinolones ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, and moxifloxacin are typically first-line therapy in the United States for adults 18 years of age and older [32,39,42]. These agents are bactericidal against the plague bacillus. The recommended alternative agents doxycycline and chloramphenicol are bacteriostatic but effective [42]. Historically, streptomycin was the treatment of choice for plague, but the advent of equally effective and less toxic aminoglycosides has meant that streptomycin is no longer widely available in the United States [39]. In a retrospective analysis of 50 patients reported between 1985 and 1999, gentamicin alone or in combination with doxycycline was as effective as streptomycin for treatment of human plague [43]. Tetracyclines, sulfonamides, and chloramphenicol have been used to treat plague successfully for many years. A review of published cases of plague found that survival rates of patients treated with tetracycline, sulfonamide, or chloramphenicol monotherapy were 90%, 70%, and 75%, respectively [19]. The Working Group and the CDC recommend adding chloramphenicol (25 mg/kg IV, four times daily) for patients with plague meningitis. Supportive therapy includes maintaining fluid levels with IV fluids and monitoring of the patient's hemodynamic status [32]. The duration of antibiotic treatment is 10 to 14 days total [42]. Oral therapy may be substituted when the patient has improved. If fever recurs after a favorable initial therapeutic response, the patient may have secondary infection, drug fever, or a suppurative bubo that requires incision and drainage [37]. The CDC provides guidance regarding the specific antibiotic regimens for adults and children, including postexposure prophylaxis and links to additional information on antimicrobial therapy of plague [39,42].

In a mass casualty setting, ciprofloxacin (750 mg orally, twice daily) or levofloxacin (750 mg daily) are recommended and should be continued for 10 to 14 days [39,42]. Tetracyclines and chloramphenicol are alternative choices [42]. The CDC recommends that postexposure prophylaxis with a first-line antimicrobial (e.g., ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, doxycycline) be considered for persons who had close (i.e., less than 6 feet), sustained contact with a patient with pneumonic plague and were not wearing adequate personal protective equipment. Antimicrobial postexposure prophylaxis also can be considered for laboratory workers accidentally exposed to infectious materials and persons who had close (i.e., less than 6 feet) or direct contact with infected animals, such as veterinary staff, pet owners, and hunters. Postexposure prophylaxis should be given for seven days [42].

For bubonic plague, general care includes hospitalization and use of drainage and secretion precautions for 48 hours after the start of effective therapy. With pneumonic plague, strict droplet and standard precautions against airborne spread are required until 48 hours of appropriate antibiotic therapy have been completed with favorable clinical response [44]. Anyone who was in the household or had face-to-face contact with pneumonic plague-infected patients should be provided chemoprophylaxis [37].

Private rooms are recommended when possible. If not available, patients with similar symptoms and the same presumptive diagnosis (i.e., pneumonic plague) should be in the same room [44]. Maintain spatial separation of at least 3 feet between infected patients and others whenever possible. Avoid placement of patients with droplet precautions in the same room with immunocompromised patients. Special air handling is not necessary, and doors may remain open. Limit movement and transport of patients on droplet precautions to essential medical purposes only. Minimize dispersal of droplets by placing a surgical-type mask on the patient when transport is necessary [9,32].

Vectors and reservoirs (i.e., fleas and rodents, respectively) of disease should be eliminated to prevent a disease cycle in the local area [9]. Flea barriers should be considered for use in patient care areas.

Prior to 1999, a licensed, killed, whole-cell vaccine was available in the United States for use in those considered to be at risk of exposure to plague [9]. The vaccines that have been used have not been effective against pneumonic plague [32,45]. At this time, there is no vaccine available, although research is taking place to develop one that is suitable. Much of this research is occurring outside the United States; however, vaccines have been developed and tested by the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases [9]. A fusion protein vaccine has been found to protect mice for up to one year [46,47]. In 2017, the FDA granted orphan drug designation to DynPort Vaccine Company LLC for its recombinant rF1V plague vaccine. The company is developing the vaccine on behalf of the Department of Defense [48].

Tularemia is primarily a zoonotic disease of rural populations, although occasional urban cases have occurred. The infective organism, Francisella tularensis, is a gram-negative intracellular coccobacillus with very marked pathogenic infectivity [49]. Humans can become infected by ingestion of or contact with contaminated water, food, or soil. Transmission can also occur through inhalation of aerosols, handling of infected animal tissues or fluids, and the bites of infective arthropods (usually ticks). Person-to-person transmission has never been reported [49,50].

Tularemia is one of the most infectious diseases known; as few as 10 F. tularensis bacteria can cause disease in humans [49,50]. Consequently, it has been widely exploited as a weapon of bioterror. The Japanese studied it for use between 1932 and 1945, the Soviet Union may have used it on the Eastern Front in World War II, and the United States possessed a 450 kg weaponized dry-form stockpile until the use of biologic arsenals was eliminated [49,51]. The most probable dissemination of F. tularensis as a weapon would be as an aerosol [50]. In fact, epidemics have occurred after harvests in Northern Europe, where the organism became aerosolized and infected hundreds of people. The organism is quite hardy and can survive for prolonged periods of time in water, mud, and animal carcasses. Even frozen, F. tularensis is highly infectious, and laboratory workers have become infected while inspecting incubation plates [49]. It is estimated that a 50 kg aerosolized release over a 5 million inhabitant metropolitan area could infect 250,000 people and kill nearly 20,000 [51].

There are several classification systems for clinical tularemia. One such system categorizes tularemia as either ulceroglandular (occurring in the majority of patients) or typhoidal [52,53]. Ulceroglandular disease is characterized by lesions on the skin or mucous membranes (including conjunctiva), lymph nodes larger than 1 cm, or both. Typhoidal tularemia describes systemic manifestation of the disease without skin or mucous membrane lesions [49,53]. In addition to these two types, pneumonic tularemia, caused by inhalation and primarily manifesting as pleuropneumonic disease, also occurs [49,53]. Pneumonic tularemia is often considered a type of typhoidal tularemia.

As noted, typhoidal tularemia is an acute, nonspecific febrile illness and is not associated with prominent lymphadenopathy or skin lesions [49]. This type of tularemia is caused by inhalation or ingestion of bacilli and may involve significant gastrointestinal symptoms. It is believed that typhoidal tularemia would be most prevalent during an act of bioterrorism [52].

The incubation period is usually 3 to 6 days (range: 1 to 21 days), although aerosol exposures have been shown to result in incapacitation in the first day [49,52]. Symptoms may include fever with chills, headache, myalgia, sore throat, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and cough [52,53]. Patients may develop tularemia sepsis, which can be fatal. This syndrome manifests with hypotension, respiratory distress syndrome, renal failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and shock [52].

Pneumonic tularemia results from inhalation of infected aerosols or spread of existing untreated disease. Hemorrhagic inflammation of the airways is an early sign [49]. Radiologic studies show pleuritis with adhesions and effusions and peribronchial infiltrates; hilar lymphadenopathy is also common [49,52]. These signs, however, are not always present. Patients may develop acute respiratory distress syndrome and require mechanical ventilation [52].

Ulceroglandular tularemia is generally caused by an arthropod bite or handling a contaminated animal carcass [49,53]. A local papule develops at the inoculation site, with progression to a pustule and ulceration within a few days. The ulcer may be covered by an eschar [49,53]. Lymphadenopathy develops in 85% of patients [52]. The nodes are usually tender and 0.5–10 cm in diameter [52,53]. Affected nodes may become fluctuant, rupture, or persist for months to years [52]. In most cases, there is a single ulcer, 0.4–3.0 cm in diameter, with raised borders. Other symptoms include fever, chills, headache, and cough [52].

Ulceroglandular tularemia can also be complicated by oculoglandular disease or oral/pharyngeal involvement. Oropharyngeal tularemia is caused by ingestion of contaminated food, water, or droplets and results in severe throat pain, exudative pharyngitis, stomatitis, or tonsillitis [52,54]. Oculoglandular tularemia, caused by direct contamination of the eye, is characterized by purulent conjunctivitis and pre-auricular adenopathy on the involved side of the face [49,53].

There are several biologic variants or subspecies of F. tularensis. Type A is considered to be more virulent, while the European variant, F. tularensis biovar palaearctica, typically causes a more mild form of the disease [49]. Both types can be identified with DFA analysis, which gives a presumptive diagnosis of tularemia. Direct examination with gram stain may not be helpful because F. tularensis is a weakly staining pleomorphic gram-negative coccobacillus, making it difficult to identify [52,55]. Due to the strong possibility of laboratory workers becoming infected, routine analysis should take place in biosafety level-2 (BSL-2) facilities and handling of identified cultures should be in a BSL-3 lab [49,52,53]. F. tularensis can be grown in appropriate cultures but may not be identifiable until after 48 hours. Antibody or other serologic tests and/or cultures are necessary for confirmation of the diagnosis [53]. Antibody detection assays include ELISA, tube agglutination, and microagglutination, but significant antibodies may not appear until 10 to 14 days after the onset of the illness [52,53]. A positive DFA test on a culture can confirm the diagnosis.

All forms of tularemia may be treated with streptomycin or, alternatively, gentamicin for 10 to 14 days [9,49,52,56]. Gentamicin may be more readily available and easier to administer. Also, because streptomycin has been associated with ototoxicity in fetuses, gentamicin is the drug of choice for pregnant women [49,52]. In a mass casualty situation, doxycycline or ciprofloxacin are preferred [49]. Doxycycline should be continued for 14 to 21 days, due to risk of relapse [9]. The use of chloramphenicol is generally discouraged due to the associated serious side effects; however, the Working Group states that it is an alternative, although not FDA approved [49,50]. Doxycycline and ciprofloxacin are recommended by the Working Group for mass casualty and confined cases, although ciprofloxacin is not FDA approved for this indication [49,50,57]. Dosages are similar to those for plague, except chloramphenicol, the dose for which is 15 mg/kg IV, four times daily [32,49,50].

Cases of tularemia meningitis require special treatment, as the penetration of streptomycin or gentamicin into cerebrospinal fluid is suboptimal [52]. Chloramphenicol 25 mg/kg IV, four times daily, plus an aminoglycoside (particularly streptomycin) is the recommended treatment for meningeal infections [52,58]. Doxycycline has also been used to treat tularemia meningitis [58].

Because tularemia is not believed to be transmissible from person to person, respiratory isolation rooms are not required [52]. In general, standard precautions are sufficient [49,52]. Ulcers, when present, should be covered and contact isolation maintained, as F. tularensis remains present in such lesions for more than a month [52]. All postmortem procedures likely to cause aerosols should be performed using respiratory precautions or avoided altogether [20,49,52]. It must be reinforced that significant personal safety precautions be taken when handling tissues or other samples possibly containing F. tularensis because it is the second most common cause of laboratory-associated infections in the United States [55,59].

A live, attenuated tularemia vaccine was available as an investigational new drug (IND), but it was not approved by the FDA [49,50]. An attenuated vaccine has been used in the former Soviet Union to immunize tens of millions of people [60]. The live vaccine strain has proven effective in preventing laboratory-acquired tularemia, although its effectiveness in preventing pneumonic tularemia is limited. The degree of protection depends upon the magnitude of the challenge dose [9,49]. Research is being conducted to find a suitable vaccine that can be used widely in the United States [61]. Currently, there is no effective vaccine available [9,50,53].

It is estimated that smallpox killed 500 million people worldwide in the 20th century, but a successful ring vaccination campaign ended outbreaks by 1980 [11]. The variola virus (the smallpox causative organism) is quite stable in the environment and is highly infectious when spread by the respiratory route. It is also spread easily through direct contact. The likelihood of contracting smallpox approaches 90% for susceptible persons exposed to someone with active infection. The case fatality rate is approximately 30% among those who have not been vaccinated [62].

Variola can be used as a biologic weapon in aerosol form or deposited onto surfaces. Because smallpox vaccination of the general population in the United States was discontinued in the 1980s, the use of the smallpox virus as a weapon constitutes a large threat, especially because certain countries may be harboring stockpiles of the agent.

The use of smallpox as a biologic weapon has a long history. In 1520, the Aztecs captured one of Cortés' men who was infected with smallpox. The resulting epidemic aided the Spaniards in defeating the Aztecs.

It is commonly believed that contaminated blankets were given to American natives by the U.S. Army to assist in their conquest during the French and Indian War [63,64]. Although it is clear that this approach was discussed among military officers, it is unclear whether intentional infection through the use of "smallpox blankets" was ever carried out. Some scholars propose other routes of transmission leading to smallpox outbreaks among indigenous Americans, such as raids on infected European settlements by natives, non-military European contact, grave robbing, and contact with Mexican traders [64].

Variola virus belongs to the family Poxviridae, subfamily Chordopoxvirinae, and genus Orthopoxvirus. It is a single, linear, double-stranded DNA molecule of 140–375 kb pairs. It replicates in cell cytoplasm. Electron micrographs show that variola viruses are shaped like bricks. This brick shape distinguishes variola from varicella zoster, the virus that causes chickenpox and shingles [65].

Smallpox is transmitted from one person to another by droplets. Droplets containing the variola virus can be transmitted through face-to-face contact while talking, singing, coughing, or sneezing. It is also transmitted by saliva through sharing food or drink and kissing on the mouth. These activities contribute to a more vulnerable population than in the days before eradication.

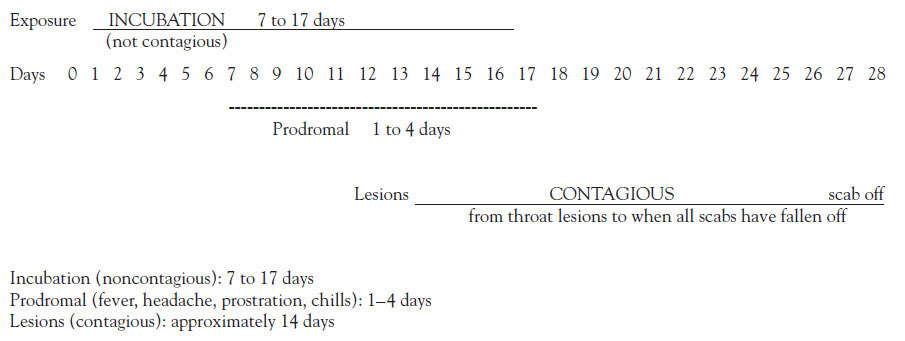

The virus is not shed during the incubation period, which can be from 7 to 17 days but most commonly is 10 to 14 days (Figure 1) [66]. During the incubation period, the virus enters the respiratory tract, seeds the mucous membranes, passes quickly to the lymph nodes, and multiplies in the reticuloendothelial system [65]. It is believed that only a few virions (virus particles) are sufficient to cause infection [67].

The prodromal phase, which follows the incubation period, lasts from one to four days, begins abruptly, and is characterized by a fever of at least 38.5–40.5 degrees C (101–105 degrees F) and at least one of the following [66,68,69]:

Prostration

Severe (splitting) headache (90%)

Backache (90%)

Chills (60%)

Vomiting (50%)

Delirium (15%)

Abdominal colic (13%)

Diarrhea (10%)

Convulsions (7%)

At the end of the prodromal phase (about 24 hours before the skin rash erupts), minute red spots (the enanthem) appear on the tongue and soft palate. The patient may complain of a sore throat, as lesions may also be present lower in the respiratory tract. When the lesions in the mouth and pharynx open and release the virus, the patient is contagious. Patients are most contagious for the first week but can still transmit the disease until all the epidermal scabs from the skin lesions have fallen off, usually in approximately 21 to 28 days.

The smallpox rash erupts at the end of the prodrome. A few lesions usually appear first on the face, especially on the forehead. These are called the "herald spots." Occasionally, the rash is first seen on the forearms. Lesions tend to appear on the proximal portions of the extremities and the trunk, and then on the distal portions of the extremities. However, the rash usually progresses so quickly that it is apparent on all parts of the body within 24 hours and the patient does not notice how the rash progressed. Normally, more lesions appear over the next one or two days, possibly followed by a few fresh lesions later. Generally, the rash is distributed in a "centrifugal" pattern. The rash is most dense on the face and denser on the extremities than on the trunk. It is more prominent distally than proximally and on the extensor rather than on the flexor surfaces. There may also be lesions on the palms and soles [66,68].

The rash of smallpox passes through stages of macules, papules, and vesicles. Mature smallpox lesions are round, well-circumscribed vesicles that are deep-seated and firm. As they continue to develop, the lesions become umbilicated, having a central "naval-like" depression. The more confluent the lesions, the poorer the prognosis [66]. Another distinguishing feature of the smallpox rash is that the lesions on any specific area of the body are all in the same state of development, meaning that they are all simultaneously vesicles, pustules, or umbilicated lesions [66]. In contrast, the rash of chickenpox starts as a vesicle on top of erythema. Chickenpox lesions arrive in "crops," so in any one area of the body there will be a variety of vesicles, pustules, and crusts (scabs). The palms and soles are rarely involved, and patients are rarely toxic or moribund [69].

There are many possible secondary complications in smallpox. Most are due to viral activity in an unusual site or secondary bacterial infections. Smallpox can affect several systems. The skin lesions can become infected with bacteria, but the broad-spectrum antibiotics available today and good hygiene will prevent many of these secondary infections. Mild conjunctivitis at the time of the skin eruptions is part of the disease; however, corneal ulceration and keratitis may occur, causing blindness [70]. Mostly, corneal lesions occur in patients with confluent or semiconfluent rashes. The joints may be involved, causing arthritis in approximately 1.7% of survivors [70,71]. The elbow is the most commonly affected joint. Respiratory complications may develop around day 8, and pulmonary edema is fairly common in hemorrhagic and flat-type smallpox [70,71]. However, cough is a rare symptom in smallpox. Encephalitis occurs in 1 in 500 cases, usually appearing between day 6 and 10 [70]. If the patient recovers, the recovery is slow but usually complete. The sequelae in persons who recover from smallpox, in order of frequency, are facial pockmarks, blindness (due to corneal scarring), and limb deformities (due to osteomyelitis and arthritis) [68].

Laboratory analysis for the distinct diagnosis of smallpox is not always easy because the pox viruses can only be rapidly distinguished from one another by PCR assay or electron microscopy (EM) [72,73]. For EM, skin samples (e.g., scrapings from papules, vesicular fluid, pus, or scabs) may be collected. This can provide rapid identification of the pox viruses, including smallpox, cowpox, and monkeypox. Skin samples may also be used for agar gel immunoprecipitation, immunofluorescence, or PCR assay. In the event of known exposures, early postexposure (0 to 24 hours) nasal swabs and induced respiratory secretions may be collected for viral culture, fluorescent antibody assay, and PCR assay. After two days, blood may be collected for viral culture. Serologic tests may be useful for confirmation or early presumptive diagnosis [72]. The CDC has outlined the type of specimen to be collected according to the stage of the disease [73].

The treatments for smallpox are limited [74,75,76]. Therefore, the development of smallpox vaccine has been a significant medical achievement. The severity of disease can be greatly lessened or prevented by administration of vaccine up to four days postexposure [74]. There is some evidence that vaccination four to seven days postexposure can prevent or somewhat lessen the severity of the disease [75].

Because there have been no natural cases of smallpox since 1977, the antivirals currently available have never officially been tested on human smallpox infections. In 2018, the FDA approved the first medication for the treatment of smallpox—tecovirimat [77]. The efficacy of oral tecovirimat was established in two placebo-controlled, nonhuman primate models (monkeypox and rabbitpox) in which treatment was associated with greater than 90% survival [78]. The same investigators included a randomized placebo-controlled safety trial in human adult volunteers, showing that tecovirimat was well-tolerated and that most reported adverse events were mild. The antiviral agent cidofovir (used to treat cytomegalovirus retinitis in immunocompromised patients) has also been used to effectively reduce morbidity and mortality of human smallpox in animal models and has been used to treat severe adverse reactions to the smallpox vaccine [76,79]. Cidofovir may only be used under IND protocol for the treatment of either vaccination reaction or smallpox infection [75]. Kidney failure has occurred in some patients with only one or two doses of cidofovir [80].

Vaccinia immune globulin (VIG) has been used in the past to treat smallpox and was administered when vaccinating patients at high risk for an adverse reaction (e.g., those with inflammatory skin conditions); a new purified IV form (VIG-IV) is available from the CDC [79]. Indications for use include postvaccination moderate-to-severe generalized vaccinia, progressive vaccinia, eczema vaccinatum, and certain accidental implantations; VIG-IV is the recommended first-line treatment for these conditions [79]. Concomitant use of VIG-IV is not recommended when vaccinating susceptible individuals because efficacy has not been studied in clinical trials and stores of the antibody are low [79]. For active infections, VIG-IV may shorten the duration of the disease [81].

Management of active infections relies heavily on supportive care. This consists of [70,71]:

Skin care

Monitoring for and treatment of complications

Monitoring and maintaining fluid and electrolyte balance

Isolation of the patient to prevent transmission of variola virus to nonimmune persons

Smallpox patients should be considered infectious until scabs separate, usually about three weeks from the time of infection. Patients should be handled using standard precautions, and isolation with droplet and airborne precautions should be exercised for infected individuals and all contacts for a minimum of 16 to 17 days following exposure. In cases of mass casualties, isolation in the home or other non-hospital facilities should be considered where possible, as the risk for transmission is high and few hospitals will have enough negative pressure rooms for proper isolation. Immediate vaccination, if available, should be given to all medical personnel. Outside of the hospital setting, patients and household contacts should wear an N95 mask. Caregivers should wear disposable gowns and gloves as well. Bed linens, clothing, and other exposed articles must be sterilized or incinerated [72].

As of 2023, there are two licensed smallpox vaccines [82]. Until 2007, the only available vaccine was Dryvax (approved by the FDA in the early 1930s), which was manufactured from a sample of the New York City Board of Health strain of vaccinia grown on calf skin and freeze dried for storage and use. However, Dryvax is no longer manufactured [82]. In 2007, a second-generation smallpox vaccine, ACAM2000, was approved by the FDA [82,83]. This vaccine is derived from a clone of Dryvax, purified and produced using cell culture technology rather than by using live animal models [82,84]. The biologic profile is similar to Dryvax, and the vaccine has equivalent efficacy and tolerability. A third-generation smallpox vaccine, IMVAMUNE, was approved for manufacture by the FDA in 2010, and as of 2014, at least 20 million doses had been delivered to the CDC Strategic National Stockpile (SNS) [85]. The IMVAMUNE vaccine is generated from a highly attenuated, replication-deficient vaccinia strain (modified vaccinia Ankara [MVA] strain) [83; 86]. Aventis Pasteur Smallpox Vaccine is an investigational vaccine stored in the SNS. It has an efficacy and safety profile anticipated to be similar to ACAM2000 [86]. It would be made available under an IND in case of a smallpox emergency in circumstances where ACAM2000 is depleted, not readily available, or contraindicated [86]. A second MVA-based vaccine against smallpox and monkeypox was approved in 2019 and is included in the SNS [87].

It should be noted that although these vaccinations are called "smallpox vaccinations," they do not contain any smallpox virus and cannot transmit the disease. However, the vaccines can transmit vaccinia and can produce life-threatening adverse events in some cases [75]. The FDA has required "black box" warnings to be included with the smallpox vaccines due to the possibility of encephalitis, myopericarditis, ocular complications, and skin and systemic infections (i.e., progressive vaccinia, generalized vaccinia, severe vaccinial skin infections, and erythema multiforme major) [57]. The goal of the third-generation vaccine is to provide complete protection from the disease (i.e., equal to that of ACAM2000) while increasing the safety profile. It is estimated that in a widespread vaccination scenario, approximately 25% of the population would be at risk for developing complications of ACAM2000 [83,85]. In a safety study of an earlier version of MVA conducted in Germany, 120,000 people were given the vaccine with few observed complications. The efficacy of IMVAMUNE in humans is thought to be equivalent to that of ACAM2000 based on animal testing using the FDA "animal rule," which states that animal studies to verify efficacy are valid when it is impractical or unethical to use human test subjects [83]. Clinical trials to assess the safety of IMVAMUNE are ongoing.

The "ring vaccination" strategy will be the first-line strategy in a smallpox emergency. It vaccinates the contacts of patients with confirmed smallpox and also those who are in close contact with those contacts. This may include [88,89]:

Face-to-face close contacts (≤6.5 feet or 2 meters) or household contacts (without contraindications to vaccination) to smallpox patients after the onset of the smallpox patient's fever, and nonhousehold members with three or more hours of contact with a case with rash

Persons exposed to the initial release of the virus (if the release was discovered during the first generation of cases and vaccination may still provide benefit)