Dietary supplement use is increasingly common, with nearly 60% of survey respondents reporting use of a dietary supplement in the previous month, according to recent data. Groundbreaking surges in sales have been fueled by the COVID-19 pandemic. Patients may be asking about popular herbal supplements, including safety and potential uses. Healthcare professionals should be well informed about these top-selling herbal supplements so that they can provide evidence-based recommendations and appropriate safety warnings.

This course is designed for dental professionals whose patients are taking or are interested in taking herbal supplements.

The purpose of this course is to provide dental professionals in all practice settings the knowledge necessary to increase their understanding of the most popular herbal supplements and to better counsel patients regarding their use.

Upon completion of this course, you should be able to:

- Describe characteristics of both the supplement market and some top-selling herbal supplements.

- Discuss the evidence for and safety considerations regarding the use of elderberry, apple cider vinegar (ACV), echinacea, and ashwagandha for common indications.

- Outline evidence for and common adverse effects of turmeric.

- Review special considerations related to the use of elderberry, turmeric, ACV, echinacea, and ashwagandha.

Chelsey McIntyre, PharmD, is a clinical pharmacist who specializes in drug information, literature analysis, and medical writing. She earned her Bachelor of Science degree in Genetics from the University of California, Davis. She then went on to complete her PharmD at Creighton University, followed by a clinical residency at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP). Dr. McIntyre held the position of Drug Information and Policy Development Pharmacist at CHOP until her move to Washington state in 2017, after which she spent the next six years as a clinical editor for Natural Medicines, a clinical reference database focused on natural products and alternative therapies. She continues to create rigorous professional analysis and patient education materials for various publications while also practicing as a hospital pharmacist. Her professional interests include provider and patient education, as well as the application of evidence-based research to patient care.

Contributing faculty, Chelsey McIntyre, PharmD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationship with any product manufacturer or service provider mentioned.

Mark J. Szarejko, DDS, FAGD

The division planner has disclosed no relevant financial relationship with any product manufacturer or service provider mentioned.

Sarah Campbell

The Director of Development and Academic Affairs has disclosed no relevant financial relationship with any product manufacturer or service provider mentioned.

The purpose of NetCE is to provide challenging curricula to assist healthcare professionals to raise their levels of expertise while fulfilling their continuing education requirements, thereby improving the quality of healthcare.

Our contributing faculty members have taken care to ensure that the information and recommendations are accurate and compatible with the standards generally accepted at the time of publication. The publisher disclaims any liability, loss or damage incurred as a consequence, directly or indirectly, of the use and application of any of the contents. Participants are cautioned about the potential risk of using limited knowledge when integrating new techniques into practice.

It is the policy of NetCE not to accept commercial support. Furthermore, commercial interests are prohibited from distributing or providing access to this activity to learners.

Supported browsers for Windows include Microsoft Internet Explorer 9.0 and up, Mozilla Firefox 3.0 and up, Opera 9.0 and up, and Google Chrome. Supported browsers for Macintosh include Safari, Mozilla Firefox 3.0 and up, Opera 9.0 and up, and Google Chrome. Other operating systems and browsers that include complete implementations of ECMAScript edition 3 and CSS 2.0 may work, but are not supported. Supported browsers must utilize the TLS encryption protocol v1.1 or v1.2 in order to connect to pages that require a secured HTTPS connection. TLS v1.0 is not supported.

The role of implicit biases on healthcare outcomes has become a concern, as there is some evidence that implicit biases contribute to health disparities, professionals' attitudes toward and interactions with patients, quality of care, diagnoses, and treatment decisions. This may produce differences in help-seeking, diagnoses, and ultimately treatments and interventions. Implicit biases may also unwittingly produce professional behaviors, attitudes, and interactions that reduce patients' trust and comfort with their provider, leading to earlier termination of visits and/or reduced adherence and follow-up. Disadvantaged groups are marginalized in the healthcare system and vulnerable on multiple levels; health professionals' implicit biases can further exacerbate these existing disadvantages.

Interventions or strategies designed to reduce implicit bias may be categorized as change-based or control-based. Change-based interventions focus on reducing or changing cognitive associations underlying implicit biases. These interventions might include challenging stereotypes. Conversely, control-based interventions involve reducing the effects of the implicit bias on the individual's behaviors. These strategies include increasing awareness of biased thoughts and responses. The two types of interventions are not mutually exclusive and may be used synergistically.

#58080: Top-Selling Herbal Supplements

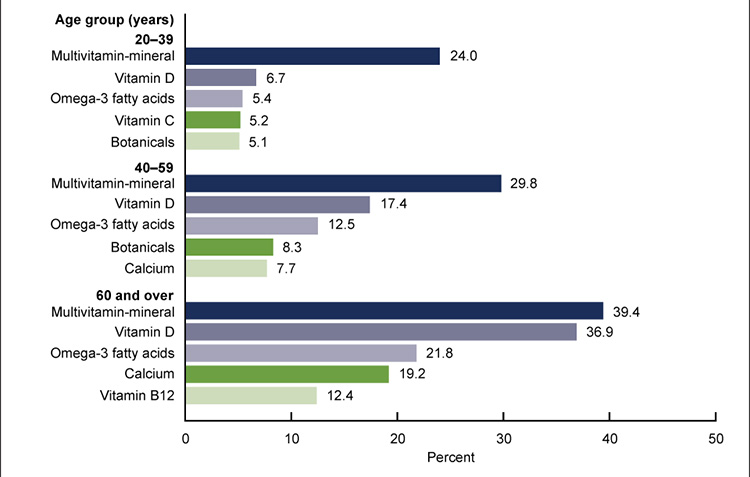

Dietary supplements are products other than tobacco that are intended to supplement the diet through means of ingestion. Examples of common types of dietary supplements include vitamins, minerals, herbals, and amino acids. Dietary supplement use is increasingly common. In 2017–2018, nearly 60% of adults 20 years of age or older in the United States reported using a dietary supplement in the previous month. Women tend to use more supplements than men, and overall dietary supplement use increases with age. Women 60 years of age or older are among the greatest users of dietary supplements. Herbal supplements, often referred to as botanicals, are among the most common dietary supplements used by those 20 to 59 years of age (Figure 1) [1].

In 2020, U.S. supplement sales soared, surpassing $10 billion for the first time ever. U.S. retail sales of herbal supplements totaled $11.3 billion, representing a 17.3% increase from the previous year. This surge was particularly fueled by the sales of supplements touted for immune health, stress relief, and heart health, likely related to the COVID-19 pandemic sweeping the globe [2].

The focus of this course will be on the following top-selling herbal supplements, the research behind their uses, and practical safety concerns: apple cider vinegar (ACV), ashwagandha, echinacea, elderberry, and turmeric.

ACV is the fermented juice from crushed apples. It contains pectin, vitamins, minerals, and significant quantities of either acetic or citric acid. ACV is chemically different from vinegars derived from other sources [3].

ACV is most commonly used in cooking, especially for salad dressing, but has also been promoted for weight loss, regulation of blood sugar, blood pressure, digestive health, cholesterol reduction, immune support, skin care, and many other uses. In mainstream retail outlets, consumers spent more than $79 million on ACV supplements in 2020, representing an increase of 134% from the previous year [3].

In addition to its traditional liquid form, ACV is also now available in solid dosage forms, including tablets and gummies. The bioactive properties of ACV are influenced by multiple factors, including the raw materials, production method, and geographical conditions [3].

ACV is produced by several methods, including the slower artisanal method and the commercial/industrial method. The artisanal method uses apples and naturally occurring yeast microflora to ferment apple sugars in the absence of oxygen. Wood barrels introduce oxygen, which allows naturally occurring acetic bacteria to convert alcohol into acetic acid. The commercial method adds yeast to apple juice for alcohol production, followed by the incorporation of oxygen via a high-speed motor, which allows acetic bacteria to transform alcohol into acetic acid [3].

The constituents of ACV occur in different concentrations depending on the method. An analysis of ACV products suggests that the artisanal method produces a higher pH and higher concentrations of mineral elements, vitamin C, total phenolic content, and total flavonoid content. In vitro research suggests that ACV produced via the artisanal method has greater antioxidant activity and may have greater inhibitory activity against alpha-glucoside and alpha-amylase enzymes than ACV produced via the commercial method [3].

The process of producing ACV results in the formation of the "mother." The mother is composed of bacteria and yeast. ACV products that are cloudy in appearance and are described as raw or unfiltered typically contain the mother. These products are often labeled as organic or may include a statement about the presence of the mother. Raw or unfiltered ACV products are often preferred for culinary use because they tend to have a more intense apple flavor [3].

People sometimes incorrectly perceive raw or unfiltered ACV products to be spoiled because of their cloudy appearance, and for this reason, they might have a preference for an ACV product that is not cloudy. ACV products that are clear in appearance and are described as filtered or pasteurized typically do not contain the mother [3]. While the health benefits of ACV are often attributed to products containing the mother, this does not seem to be backed by research.

In the United States, there is no regulatory standard for identifying vinegar products. Liquid ACV for food is standardized based on acidity content, usually ranging from 4% to 8%. A laboratory analysis of commercially available ACV tablets shows wide variation in terms of content and acidity. Amounts of acetic acid range from about 1% to nearly 11% and amounts of citric acid range from 0% to nearly 19%. Buyers should be beware that amounts of constituents provided on product labels were not always consistent with laboratory findings [3].

In animal models of diabetes, ACV significantly reduces glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c). ACV is thought to lower blood glucose by delaying the gastric emptying rate and/or preventing carbohydrate breakdown. Findings in humans are not as robust [3].

A small clinical study in patients with type 2 diabetes and dyslipidemia shows that taking ACV 10 mL twice daily in water for eight weeks reduces fasting blood glucose levels, but not insulin levels or insulin sensitivity, when compared with control. A very small clinical study in patients with varying degrees of insulin sensitivity shows that taking ACV 20 grams daily with a meal increases postprandial insulin sensitivity and reduces changes in insulin levels after a meal in patients with insulin resistance, but not in patients with type 2 diabetes [3].

A meta-analysis of lower-quality clinical studies in a diverse population, including patients with overweight or obesity and patients with type 2 diabetes, shows that taking ACV 15–770 mL daily for 30 to 90 days reduces fasting blood glucose levels by about 8 mg/dL and HbA1c by 0.5% when compared with water, another beverage, or no beverage control. However, these beneficial effects on glycemic indices are not observed in subgroup analyses of patients with type 2 diabetes [3].

Overall, most clinical studies suggest that oral ACV is not beneficial for improving glucose control in patients with type 2 diabetes, but results may be limited by lack of blinding in many studies, likely because the potent taste of ACV is difficult to mask. It is also unclear if the formulation of ACV alters its effects. A small crossover study in healthy adults found a modestly greater reduction in postprandial glucose with the use of liquid ACV (providing 1.25 grams of acetic acid) when compared with whole or crushed ACV tablets (providing 1.5 grams of ACV) [3].

Tell patients to rely on standard, proven therapies for the treatment of diabetes. ACV does not have enough evidence to support consistent benefits on blood glucose control.

There has been interest in using oral ACV for prediabetes, but there is not enough reliable information about the clinical effects of ACV for this indication [3].

While ACV is often promoted for weight loss, the research is limited to just a few small studies. ACV seems to have different effects in healthy adults and in patients with overweight or obesity.

A very small clinical study in healthy adults shows that taking ACV 30 mL daily for four days has no effect on energy expenditure, at rest or during exercise. ACV also did not alter the use of carbohydrates or fats as energy sources [3].

A small clinical study in patients with overweight or obesity shows that, compared with a calorie-restricted diet alone, taking ACV 15 mL twice daily in combination with a calorie-restricted diet for 12 weeks [3]:

Controls appetite

Reduces body weight by 4 kg, compared with 2 kg

Reduces body mass index (BMI) by 2 kg/m2, compared with 1 kg/m2

Reduces hip girth by 6 cm, compared with 3 cm

For patients who are overweight or obese and are interested in trying ACV for its weight loss effects, a trial seems reasonable, but tell them to keep in mind that a small study showing beneficial effects had patients taking ACV in combination with a calorie-restricted diet.

Orally, ACV is well tolerated in the amounts found in foods. It also seems to be well tolerated when used for medical purposes for up to 12 weeks. But the use of larger amounts or for longer durations may be unsafe [3].

Because ACV is so acidic, drinking it straight can cause erosion of tooth enamel and might also exacerbate acid reflux. It is recommended that ACV be diluted in water prior to ingestion or at least followed up with ingestion of a sufficient amount of water if taken undiluted [3].

While topical use of ACV has been suggested for acne, wound disinfection, eczema, dandruff, shingles, insect bites, and sunburns, topical application may actually be unsafe. Mild skin irritation is common, and multiple cases of chemical burns have been reported [3].

Ashwagandha is a small evergreen shrub found in dry areas of India, the Middle East, and Africa. The roots and berries are the parts that are used as medicine.

Ashwagandha is a well-known adaptogen. Adaptogens are substances that are theorized to help the body resist physiological and psychological stress. In Ayurvedic medicine, ashwagandha is known as a rasayana, or rejuvenator, and is used as a "nourishing agent for fatigue and deficiency of prana (the life vital energy)" [4].

Ashwagandha is the herbal supplement that experienced the greatest sales growth in the mainstream channel in 2020, with sales increasing by 185% from the previous year to a total of $32 million. Sales have quadrupled since 2018 [2].

Ashwagandha contains several active constituents, including alkaloids, steroidal lactones, and saponins. Ashwagandha is often standardized to the content of withanolides, a steroidal lactone, with concentrations ranging from 1.5% to 35%. However, it is unclear which constituents correlate to its clinical effects. Pharmacologic studies have found that ashwagandha has anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, sleep-inducing, and anxiolytic properties [4].

Ashwagandha seems to be beneficial for improving sleep in those with insomnia and in those experiencing nonrestorative sleep.

A small meta-analysis of clinical studies in a mixed population of healthy adults and patients with insomnia shows that, when compared with placebo, taking ashwagandha root extract or root and leaf extract daily for 6 to 12 weeks improves sleep quality, latency, and efficiency; total sleep time; and wake time after sleep onset. These effects were especially apparent in patients with insomnia and with doses of at least 600 mg daily for at least eight weeks, but the validity of these findings may be limited by the heterogeneity of the included studies [4].

A clinical study in patients with nonrestorative sleep shows that taking ashwagandha extract 125 mg daily for six weeks increases sleep quality by 72%, compared with only 29% in those taking placebo. Small-to-moderate improvements in total sleep time, sleep latency, and number of times awake also occurred [4].

Some researchers think that ashwagandha has a so-called "anti-stressor" effect. Some preliminary research suggests that ashwagandha suppresses stress-induced increases of dopamine receptors in the corpus striatum of the brain. It might also reduce stress-induced increases in plasma corticosterone, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and blood lactic acid. In clinical studies, oral ashwagandha seems to help reduce stress and might even reduce stress-related weight gain.

Clinical research in patients with chronic stress and in healthy patients with moderate to high levels of stress shows that taking ashwagandha root extracts 250–600 mg daily reduces perceived stress levels by 30% to 44% and decreases cortisol levels by 22% to 30% when compared with baseline, with results remaining significant when compared with placebo [4].

Another small clinical study in patients with chronic stress shows that taking ashwagandha root extract 500 mg twice daily might also prevent stress-related weight gain when compared with placebo [4].

If patients are looking to try this top-selling botanical, tell them that the best evidence for its use seems to be for sleep and stress. Be sure patients are also practicing good sleep hygiene and using healthy ways to cope with stress.

In vitro studies suggest that ashwagandha has anxiolytic effects, possibly through mimicking the actions of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA). In animal studies, ashwagandha enhanced serotonergic transmission by modulating postsynaptic serotonin (5-HT) receptors [4]. However, the effects of ashwagandha on different types of anxiety in humans are less clear.

A small clinical study in Canadian post office employees with moderate-to-severe anxiety shows that taking ashwagandha root 300 mg twice daily for 12 weeks in combination with standard psychotherapy interventions reduces anxiety scores when compared with standard psychotherapy and placebo. Another small clinical study in young, healthy adults with perceived stress shows that taking ashwagandha root and leaf extract 225 mg or 400 mg daily for 30 days improves self-reported anxiety, stress, and depression scores similarly to placebo [4].

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

A small clinical study in patients with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) taking a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) shows that taking ashwagandha root extract 1 gram daily for six weeks reduces anxiety symptoms by 48%, compared with a reduction of only 27% with placebo [4].

Another small clinical study in patients 16 years or older with GAD shows that taking ashwagandha root powder granules 4 grams three times daily for 60 days produces mild or moderate improvement in anxiety in 98% of patients, compared with 81% of those taking placebo. The lack of statistical comparison to placebo and the substantial placebo effect limits the validity of these findings [4].

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

A small clinical study in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) shows that taking ashwagandha root extract at a target dose of 120 mg daily for six weeks along with an SSRI reduces OCD symptom severity scores when compared with taking an SSRI alone. However, scores were already significantly lower at baseline in the group receiving an SSRI alone [4].

For diagnosed anxiety, GAD, and OCD, there is no substitute for standard therapy, including medications and psychotherapy. Tell patients that it is probably better to save their healthcare dollars for more proven therapies [4].

Orally, ashwagandha seems to be well tolerated. Doses of up to 1,250 mg daily for up to six months have been used with apparent safety. The safety of ashwagandha when used long-term remains unclear [4].

The most common adverse effects are gastrointestinal (GI) related, including diarrhea, GI upset, nausea, and vomiting. GI adverse effects are reported most often with large doses [4].

While topical use of ashwagandha has been suggested for some conditions, including back pain and wound healing, there is not enough information available to know if topical application is safe. So far, no adverse effects have been reported [4].

Ashwagandha seems to have sedative effects, so taking it in combination with substances that have sedative effects (e.g., benzodiazepines, other herbs and supplements with sedative properties) might increase the therapeutic and adverse effects of ashwagandha. Use caution in patients taking these combinations. [4]

Thyroid Disorders

Ashwagandha has been shown to stimulate thyroid hormone synthesis and/or secretion, increasing serum triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4) concentrations and reducing serum thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) levels [4]. This might exacerbate hyperthyroidism. Recommend that patients with hyperthyroidism or those being treated with thyroid hormones use ashwagandha with caution.

Digoxin Serum Assay

Ashwagandha might falsely increase digoxin levels on some serum assays. Withaferin A, a constituent of ashwagandha, has a similar chemical structure to digoxin and is responsible for this potential lab interaction. Immunoassays most likely to be affected include those using fluorescence polarization or microparticle enzymes [4].

Echinacea refers to the species of perennial plant closely related to sunflowers, daisies, and ragweed. The above-ground parts and the roots of three such species (Echinacea angustifolia, E. purpurea, and E. pallida) have been used as medicines. These plants range in height from 1–5 feet and have purple or pinkish-red flower petals [5].

Although these three species of echinacea are often used interchangeably, very little research has been done to compare them. While some products have been standardized to specific constituents (e.g., alkamides), the active constituents of echinacea have not been identified, so standardization may not be clinically relevant in predicting effectiveness [5].

In mainstream retail outlets, consumers spent an estimated $57 million on echinacea supplements in 2020, representing an increase of 37% from the previous year [2].

Adults

Echinacea is probably most well known for its role in preventing the common cold, though effects are generally modest. Its use for the treatment of the common cold is not as well established. The fact that these studies have evaluated the use of tinctures, extracts, and teas also makes it difficult to compare doses or even recommend the best dose for a patient to take.

Three meta-analyses have shown that taking various forms of echinacea reduces the risk of developing a cold by 10% to 58%. Another large clinical study shows that daily usage of echinacea with a dosage increase at the first sign of a cold results in 59% fewer cold episodes and 26% fewer days with cold symptoms when compared with placebo. Some clinical studies have demonstrated nonsignificant effects of echinacea on preventing colds, but these were generally smaller studies and more likely to be underpowered [5]. Small, flawed studies have shown that taking echinacea prior to intentional infection with a cold virus and continuing to take it after infection does not reduce the incidence of colds in adults [5].

In terms of lessening symptom severity or cold duration, small clinical studies have yielded some promising results, but higher-quality research shows that echinacea does not reduce symptom severity or cold duration when compared with placebo [5]. Adults might prevent some colds by taking echinacea on a situational basis (e.g., prior to traveling, during cold season), but taking it once they are already sick does not seem to help much.

Children

Studies of echinacea in children are less convincing. A clinical study in healthy children 4 to 12 years of age shows that taking echinacea 400 mg three times daily for four months reduces the occurrence of cold symptoms, respiratory complications (e.g., pneumonia, otitis media), and antibiotic prescriptions by 30%, 52%, and 62%, respectively. It also reduces the average duration of symptoms during respiratory illness by 1.4 days when compared with vitamin C 50 mg three times daily [5]. Other clinical research has found no benefit. Studies comparing echinacea to placebo in children are lacking. There is not enough evidence to recommend its use in children.

Some research shows that echinacea may exhibit antiviral activity against influenza virus. A large clinical study in adults and children at least 12 years of age with early influenza symptoms shows that taking a hot echinacea extract-based drink also containing elderberry five times daily for three days, followed by three times daily for seven days, improves recovery and respiratory complications similarly to oseltamivir. Because there was no placebo group, it is unclear if both treatments were beneficial or if the outcomes were in line with the usual self-limiting nature of influenza. It is also not clear if these effects were due to echinacea, elderberry, or the combination [5].

There is not enough clear evidence to recommend taking an echinacea-elderberry combination for influenza. While echinacea has also been studied for a broad range of other uses, the evidence for its use in many other conditions is currently limited or conflicting.

Orally, echinacea is well tolerated. Doses of up to 16 grams daily for 35 days have been used in adults, but doses vary widely depending upon the specific commercial product used [5]. The most common adverse effects are rashes and adverse GI effects, including abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea, heartburn, nausea, vomiting, and upset stomach.

Echinacea has also been used topically, including as a cream, mouthwash, and throat spray, for a variety of conditions, including burns, cold sores, psoriasis, and warts. Topical use of echinacea seems to be safe on a short-term basis [5].

Echinacea species are members of the Asteraceae family. Those with a genetic tendency toward allergic conditions (atopy), such as eczema, and those who are sensitive to other members of this family, which include ragweed, chrysanthemums, marigolds, and daisies, seem to be at higher risk for allergic reactions to echinacea [5]. Allergic reactions, including urticaria, runny nose, dyspnea, bronchospasm, acute asthma, angioedema, and anaphylaxis, have been reported with various echinacea preparations.

In a clinical study in 407 children 2 to 11 years of age, about 7% of children experienced a rash after taking echinacea. These rashes may have been caused by an allergic reaction, and there is some concern that such reactions could be severe in some children. However, another study in children 4 to 12 years of age showed that a specific E. purpurea product did not cause allergic or urticarial reactions more frequently than vitamin C [5]. Because of the risk of allergic reaction, the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency in the United Kingdom (UK) recommends against the use of oral echinacea in children younger than 12 years of age [5].

Substrates of Cytochrome P450 (CYP) 1A2 and 3A4

Echinacea might inhibit CYP1A2, increasing the levels of drugs metabolized by this enzyme. Echinacea might increase or decrease levels of drugs metabolized by CYP3A4 through inhibition of intestinal CYP3A4 and induction of hepatic CYP3A4, respectively, though there is some variability depending on the substrate. For patients taking narrow therapeutic index drugs metabolized by these enzymes, use echinacea with caution [5].

The deciduous European or black elder tree (Sambuca nigra) is the source of elderberry, a dark purple berry. This same tree is also the source of elderflowers. Both the berries and the flowers have been used in foods and beverages, but the berry is much more commonly used for medicinal purposes [6].

People often use elderberry to support immune health, and it has a long history of use in folk medicine for the treatment of colds and flu. Interestingly, Google searches for elderberry peaked in late March 2020, shortly after the COVID-19 outbreak was declared a global pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO). In mainstream retail outlets, consumers spent an estimated $275 million on elderberry in 2020, representing an increase of 150% from the previous year [2].

Elderberry products come in a variety of oral dosage formulations, including capsules, syrups, and lozenges, as well as topical dosage forms, including a mouthwash and a periodontal patch.

Influenza

In vitro, elderberry extract inhibits replication of several strains of influenza A and B. The most convincing evidence for elderberry is for the treatment of influenza in otherwise healthy adults [6].

Small clinical studies in otherwise healthy adults with influenza show that taking elderberry fruit extract within 24 to 48 hours of symptom onset improves symptoms, often within 48 hours, when compared with placebo or other control.

A small clinical study in adults and children 5 years of age or older with influenza, including those with high-risk conditions such as asthma, chronic lung disease, and heart disease, shows that taking elderberry fruit extract does not reduce the duration of symptoms when compared with placebo. The negative findings could be due to the age and baseline health status of the enrolled patients, as well as the use of symptom resolution, rather than symptom improvement, as the primary outcome [6].

As discussed, elderberry has also been studied in combination with echinacea for treating influenza symptoms, but it is unclear whether the combination is better than either ingredient alone. For otherwise healthy patients looking to try elderberry for treating influenza, recommend taking it soon after the onset of symptoms for the greatest benefit [6].

Common Cold

Elderberry has been evaluated for the treatment of influenza, but for the common cold, it has only been evaluated for prevention. Research for the prevention of the common cold is less convincing than that for the treatment of influenza [6].

A large clinical study in healthy adults traveling overseas shows that taking elderberry extract prophylactically, beginning eight days prior to air travel and continuing for four to five days after arrival to the destination, does not reduce the number of colds or impact quality of life, when compared with placebo. But the duration and severity of existing colds was reduced by two days and 58%, respectively [6].

Tell patients that taking elderberry regularly does not seem to actually prevent colds. If they still want to try it, it might make the colds they do catch shorter and a bit less severe.

Orally, elderberry extracts prepared from the ripe fruit seem to be well tolerated. Fruit extracts have most often been used in doses of up to 1,200 mg daily for two weeks or up to 500 mg daily for up to six months [6].

When adverse effects do occur, they are likely due to the ingestion of raw (i.e., uncooked) and unripe green berries. These, along with the seeds, leaves, and other plant parts, contain cyanogenic glycosides that can lead to adverse GI effects (e.g., nausea, vomiting, severe diarrhea), weakness, dizziness, numbness, and stupor. In some patients who are allergic to grass pollen, elder tree pollen might cause an allergic reaction characterized by rhinitis and dyspnea [6].

Turmeric is a spice that is commonly used in cooking. It is also used in traditional Chinese and Indian medicine. Turmeric is derived from the rhizome or root of the turmeric plant (Curcuma longa), which is a perennial herb and a member of the Zingiberaceae (ginger) family. Curcumin, a curcuminoid and the primary active constituent of turmeric, is what gives turmeric its distinctive yellow color [7].

Studies typically evaluate the use of turmeric supplements, not just ground turmeric as a spice. Supplements are often extracts and are usually standardized to curcuminoid (generally curcumin) content [7].

Although turmeric sales only increased by 3% from 2019 to 2020, turmeric sales consistently top the charts with mainstream retail outlet sales totaling close to $100 million in 2020. In addition to its status as a top-selling herbal supplement, turmeric is also incredibly well studied, especially for its anti-inflammatory benefits [2].

The oral bioavailability of curcumin is very low. Curcumin absorption appears to increase when taken [7]:

With food

With piperine (the active ingredient in black or white pepper)

In a capsule

In a liposomal formulation

In a nanoparticle formulation

In a phospholipid complex

As part of a novel turmeric matrix system

As a water-dispersible turmeric extract

Some methods of boosting curcumin absorption can be significant, resulting in a five- to seven-fold increase in absorption. Because absorption may be very specific to certain formulations, this aspect should always be considered when reviewing the evidence on the effectiveness and safety of various turmeric products [7].

Turmeric extracts have been well studied for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis.

Oral Turmeric Compared with Placebo

Meta-analyses of low- to moderate-quality studies in patients with knee osteoarthritis show that taking turmeric extracts reduces pain and improves physical function when compared with placebo, but effects were less pronounced in those with increasing age or BMI. The validity of these findings is limited by the heterogeneity of the included studies [7].

While many small- to moderate-sized individual clinical studies show that specific products containing curcumin or turmeric extracts reduce pain and analgesic use and improve functionality when compared with placebo, not all research agrees [7].

Oral Turmeric Compared with Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

A small meta-analysis in patients with knee osteoarthritis shows that taking turmeric extracts reduces pain better than an NSAID. Individual clinical studies have yielded more conflicting results. While several clinical studies show that taking turmeric extract 500 mg three to four times daily for four to six weeks reduces knee pain similarly to ibuprofen 400 mg two to three times daily, another study shows that taking turmeric extract 500 mg twice daily as an adjuvant to diclofenac 25 mg daily does not improve knee pain or function any better than diclofenac alone [7].

Oral Turmeric in Combination with Other Ingredients

Combination products that include turmeric with a number of different ingredients have also demonstrated improved pain and functionality in patients with osteoarthritis. Other ingredients that have commonly been used in conjunction with turmeric include chondroitin sulfate, glucosamine, Boswellia serrata, ginger, and devil's claw [7].

Topical Turmeric

Topical administration of turmeric has also been evaluated for knee osteoarthritis. A small clinical study in patients with knee osteoarthritis shows that twice daily topical application of curcumin 5% in a petrolatum-based ointment for 6 weeks only seems to reduce pain by about 11% when compared with placebo [7]. A trial of turmeric might be reasonable for patients experiencing joint pain attributable to osteoarthritis who are either trying to avoid or are not candidates for NSAID therapy.

Because of turmeric's well known anti-inflammatory properties, it has also been studied for rheumatoid arthritis (RA). In vitro evidence suggests some benefits specific to RA pathogenesis, but its effects on RA in clinical research are modest, at best.

One small study in patients with RA shows that taking 500 mg of a specific curcumin supplement twice daily for eight weeks improves some RA symptoms when compared with diclofenac 50 mg twice daily. Several other small studies show that taking curcumin 250 mg twice daily for three months or 400 mg three times daily for two weeks improves pain, morning stiffness, walking time, and joint swelling when compared with baseline. It is unclear if these effects were meaningful given the lack of statistical comparison to the control groups [7].

The global prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is estimated to be around 25%, so the search for potential treatments is on the rise. Clinical research in adults with NAFLD shows that taking curcumin daily reduces NAFLD severity in 30% to 79% of patients, compared with only 5% to 28% with placebo. It also attenuated additional fat deposition in the liver to only 0% to 5%, compared with 18% to 26% in those taking placebo [7]. Metabolic parameters (e.g., liver enzyme levels, BMI, blood glucose levels, HbA1c, lipid levels) also seem to be improved. Variability in some of the specific end points of individual studies might be due to differences in the formulations studied or the duration of treatment.

Emphasize that weight loss is the cornerstone of treatment for NAFLD, but if patients are asking about supplements, a trial of turmeric might provide some small, but encouraging, additional improvements [7].

Like echinacea, turmeric is of interest and has been studied for a variety of other uses, but the research for many of these other conditions is currently limited or conflicting.

Orally, turmeric seems to be safe and well tolerated. Doses of turmeric up to 3 grams daily have been used with apparent safety for up to three months. Doses of curcumin up to 8 grams daily have been safely used for up to two months [7].

Most commonly, turmeric is associated with adverse GI effects, including constipation, dyspepsia, diarrhea, distension, gastroesophageal reflux, nausea, and vomiting. Topically, turmeric also seems to be safe, though turmeric or some of its constituents can cause allergic contact dermatitis and curcumin can cause contact urticaria and pruritus [7].

Contamination is a concern with turmeric. An analysis of randomly selected turmeric products in the United States found that turmeric root products contain 2.5-fold higher concentrations of lead than turmeric-derived curcuminoid extracts. For this reason, choosing a turmeric product with a third-party quality certification is important [7].

Anticoagulant/Antiplatelet Drugs, Herbs, and Supplements

In vitro, curcumin has demonstrated antiplatelet effects. A clinical study in healthy individuals shows taking curcumin alone or in combination with aspirin does not increase antiplatelet effects or bleeding, but it is possible that the dose of turmeric used in this study was too low to see an effect [7].

Increases in the international normalized ratio (INR) have also been observed in cases of patients taking turmeric in combination with warfarin. Use turmeric with caution in patients taking anticoagulant or antiplatelet drugs, herbs, and supplements [7].

Chemotherapy Drugs

Turmeric may interact with chemotherapy drugs that generate free radicals, including alkylating agents, antitumor antibiotics, and topoisomerase I inhibitors. Lower doses of curcumin might have antioxidant effects, while higher doses might have pro-oxidant effects, resulting in inhibition or augmentation of, respectively, the cytotoxic effects of these drugs. More evidence is needed to determine what effect, if any, turmeric might have [7].

P-glycoprotein Substrates

In vitro and animal research shows that curcuminoids and other turmeric constituents can inhibit P-glycoprotein expression and activity, increasing the absorption of P-glycoprotein substrates. For patients taking narrow therapeutic index drugs that are substrates of P-glycoprotein, use turmeric cautiously [7].

Substrates of Cytochrome P450 (CYP) 1A1, 1A2, and 3A4

In vitro and animal research shows that turmeric and/or curcumin might inhibit CYP1A1, 1A2, and 3A4, increasing the levels of drugs metabolized by these enzymes, though some research disagrees. There is also some in vitro evidence that curcumin may induce CYP1A1. For patients taking narrow therapeutic index drugs metabolized by these enzymes, use turmeric cautiously [7].

Sulfasalazine

Curcumin can increase levels of sulfasalazine by more than three times, increasing both the effects and adverse effects of sulfasalazine. Dosage of sulfasalazine may require adjustment [7].

Tamoxifen

A small clinical study in patients with breast cancer taking tamoxifen shows that adding curcumin plus piperine reduces exposure to tamoxifen and its active metabolite when compared with taking tamoxifen alone. This effect was especially apparent among patients who are extensive metabolizers of CYP2D6 substrates. This interaction can potentially result in reduced clinical effects of tamoxifen. Use turmeric with caution in patients taking tamoxifen [7].

Hormone-Sensitive Cancers and Conditions

Turmeric might have mild estrogenic effects, but research is conflicting. Use turmeric with caution in patients with hormone-sensitive cancers and conditions [7].

Bleeding Disorders

Because turmeric has been reported to have antiplatelet effects, it might increase the risk of bleeding and bruising in patients with bleeding disorders. Use turmeric with caution in patients with bleeding disorders [7].

Bile Duct Obstruction and Gallstones

Because turmeric can cause gallbladder contractions, use turmeric with caution in patients with gallstones and gallbladder disease [7].

Throughout the pandemic, there have been seemingly countless claims related to the use of supplements for the prevention and/or treatment of COVID-19. In fact, all five of the supplements covered in this course have at some point been touted for the prevention and/or treatment of COVID-19. Despite these claims, there is no good evidence to support using any of these supplements for the prevention or treatment of COVID-19. Instead, recommend that patients make healthy lifestyle choices and choose proven methods for prevention (e.g., vaccination) [2].

In vitro and animal research suggests that curcumin can reduce fertility, sperm motility and density, and production of testosterone in adult Leydig cells. It can also cause degenerative changes in seminiferous tubules. Advise patients trying to conceive to use turmeric with caution [7].

When elderberry and ACV are used in typical amounts found in foods, use during pregnancy is likely safe. There is not enough information available to know if use of medicinal amounts of these botanicals is safe in pregnant patients [3,6].

When turmeric is used in typical amounts found in foods, use during pregnancy is likely safe. When used in medicinal amounts, turmeric might stimulate the uterus and increase menstrual flow. Recommend that patients avoid turmeric supplements during pregnancy [7].

Ashwagandha has abortifacient effects and is unsafe for use during pregnancy. Recommend that patients avoid ashwagandha during pregnancy [4].

Elderberry, echinacea, and ashwagandha can stimulate immune function. Theoretically, these supplements might exacerbate autoimmune disease by stimulating disease activity. For the same reason, these supplements might have drug interactions with immunosuppressant drugs. Recommend that patients with autoimmune diseases (e.g., multiple sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, RA, pemphigus vulgaris) and those taking immunosuppressants use these supplements with caution or avoid their use altogether [4,5,6].

There have been reports of liver injury with the use of some of these popular supplements. Although some herbal supplements are more prone to contamination than others, it is unclear whether reports of hepatotoxicity are the result of contamination, the actual substance itself, or some other mechanism.

There have been at least 60 reports of liver damage, including noninfectious hepatitis, cholestasis, and hepatocellular liver injury, associated with taking turmeric supplements for as little as two weeks to up to eight months. In at least 10 such cases, high dose curcumin and highly bioavailable formulations (e.g., phytosomal curcumin, piperine-containing formulations) were used, but for many cases, formulation, dosing, and duration of use were not reported. In many cases, turmeric was used concomitantly with other supplements, which may have contributed to the risk of liver damage. Most cases of liver damage resolved upon discontinuation of the turmeric supplement. Caution patients that taking turmeric, especially high-dose curcumin and highly bioavailable formulations, in combination with other drugs, herbs, and supplements that might cause liver damage can increase the risk of liver damage [7].

Cases of hepatitis have been reported rarely with echinacea use. In cases in which details were available, liver function tests normalized within one to three months following discontinuation of echinacea [5].

Several cases of liver injury have been reported with the use of typical doses, with symptoms including jaundice, nausea, abdominal pain, lethargy, and pruritus. Symptoms began within 2 to 12 weeks of taking ashwagandha and liver enzymes normalized within 1 to 5 months after discontinuation of ashwagandha. None of the cases progressed to liver failure [4].

Turmeric, ACV, and ashwagandha might decrease blood glucose levels in patients with diabetes, increasing the risk of hypoglycemia. Recommend that patients with diabetes carefully monitor blood glucose when taking these supplements, especially when they are taken in combination with antidiabetic drugs and/or other herbs and supplements with hypoglycemic potential [3,4,7].

The importance of asking patients about dietary supplement usage while obtaining their medication history cannot be understated. This is the perfect opportunity to have a nonjudgmental conversation with patients and to help identify potential safety concerns.

For patients who are not proficient in English, it is important that information regarding the benefits and risks associated with the use of dietary supplements be provided in their native language, if possible. When there is an obvious disconnect in the communication process between the practitioner and patient due to the patient's lack of proficiency in the English language, an interpreter is required. Interpreters can be a valuable resource to help bridge the communication and cultural gap between patients and practitioners. Interpreters are more than passive agents who translate and transmit information back and forth from party to party. When they are enlisted and treated as part of the interdisciplinary clinical team, they serve as cultural brokers who ultimately enhance the clinical encounter.

This is also a great opportunity to remind patients that dietary supplement oversight differs from that of prescription and over-the-counter (OTC) products regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The studies supporting the safe and effective use of supplements tend to be smaller, fewer, flawed, and less rigorous than those supporting prescription and OTC medications.

Because there is no guarantee that these products contain what is listed on the bottle and in the stated amounts, emphasize the importance of choosing a product likely to be of higher quality, such as those with third-party verification.

Verifying the quality of herbal products is difficult. The tests required and the accuracy of the resulting analyses are very different from those used for vitamins and minerals. To ensure the selection of a high-quality product, look for third-party quality certification.

In addition to inspecting manufacturing facilities for cGMP compliance at least two times in a three-year period, USP will also conduct random off-the-shelf analyses of verified products to ensure that the contents of the product match those listed on the label. This random testing holds manufacturers to a high standard.

The USP verification stamp can be found on a product's label. USP is typically considered the gold standard for dietary supplement quality verification, though their purview is limited.

Like USP, NSF is also a strong source of dietary supplement quality verification. However, general NSF certification does not necessarily imply the same quality standards as those seen with USP verification. In order for a manufacturer to list NSF certification on their website, they must pass an NSF inspection of cGMP compliance every six months. NSF does not conduct off-the-shelf analyses of products unless the manufacturer is enrolled in the "Contents Tested and Certified" or "Certified for Sport" programs. Under these programs, manufacturers are subject to random off-the-shelf testing and can place an NSF seal of approval on the product label. That seal of approval will typically state "NSF: Contents Certified" or "NSF: Certified SPORT." Unfortunately, options for NSF-certified herbal products are typically limited as well.

Dietary supplement use is increasingly common. Sales of herbal supplements seem to be largely driven by pandemic-related health concerns, but sales figures alone do not reflect the effectiveness of a supplement for a given condition, so it is important to examine the research surrounding these blockbuster supplements. Further, no supplement is without safety concerns, such as adverse effects, interactions (e.g., disease, drug, other supplements), and product quality concerns (e.g., contamination). It is imperative that clinicians provide evidence-based recommendations and appropriate safety warnings to help patients make informed decisions about their health.

1. Mishra S, Stierman B, Gahche JJ, Potischman N. Dietary supplement use among adults: United States, 2017–2018. NCHS Data Brief. 2021;(399):1-8.

2. Smith T, Majid, F, Eckl V, Reynolds CM. Herbal supplements sales in US increase by record-breaking 17.3% in 2020: sales of immune health, stress relief, and heart health supplements grow during COVID-19 pandemic. HerbalGram. 2021;(131):52-65.

3. TRC Healthcare Natural Medicines Database. Apple Cider Vinegar. Available at https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/databases/food,-herbs-supplements/professional.aspx?productid=816. Last accessed October 19, 2022.

4. TRC Healthcare Natural Medicines Database. Ashwagandha. Available at https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/databases/food,-herbs-supplements/professional.aspx?productid=953. Last accessed October 19, 2022.

5. TRC Healthcare Natural Medicines Database. Echinacea. Available at https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/databases/food,-herbs-supplements/professional.aspx?productid=981. Last accessed October 19, 2022.

6. TRC Healthcare Natural Medicines Database. Elderberry. Available at https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/databases/food,-herbs-supplements/professional.aspx?productid=434. Last accessed October 19, 2022.

7. TRC Healthcare Natural Medicines Database. Turmeric. Available at https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/databases/food,-herbs-supplements/professional.aspx?productid=662. Last accessed October 19, 2022.

1. Hadi A, Pourmasoumi M, Najafgholizadeh A, Clark CCT, Esmaillzadeh A. The effect of apple cider vinegar on lipid profiles and glycemic parameters: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2021;21(1):179. Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8243436. Last accessed October 26, 2022.

2. Elmets CA, Korman NJ, Prater EF, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapy and alternative medicine modalities for psoriasis severity measures. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(2):432-470. Available at https://www.jaad.org/article/S0190-9622(20)32288-X/fulltext. Last accessed October 26, 2022.

Mention of commercial products does not indicate endorsement.