Medication errors are a preventable cause of morbidity and mortality. Pharmacists and pharmacy technicians are often the last healthcare workers to see patients in the community before they take their medications. Medications and the processes around them are constantly changing as new drugs are introduced and technology changes. Several national organizations, as well as many individual institutions, collect data on medication errors in order to identify ways to prevent errors and improve patient safety. It's important for pharmacists and pharmacy technicians to know the causes of medication errors and practice techniques to prevent them.

This course is designed for pharmacists and pharmacy technicians who may take steps to prevent and/or manage medication errors.

The purpose of this course is to help pharmacists and pharmacy technicians in all settings develop a better knowledge base from which they can prevent medication errors.

Upon completion of this course, you should be able to:

- State why it is important to be able to define and recognize medication errors.

- Identify where medication errors may occur in the medication use process.

- Describe the possible causes of medication errors.

- Discuss strategies to prevent medication errors during dispensing.

- Recognize computer alerts that require pharmacist review.

- Explain how to use verbal order read-back.

- Review 3 methods that can be used to ensure effective patient communication.

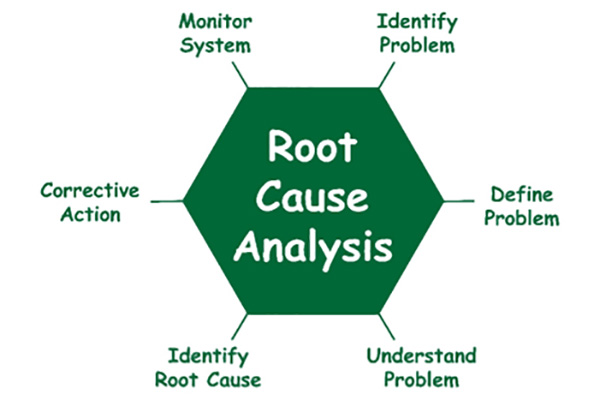

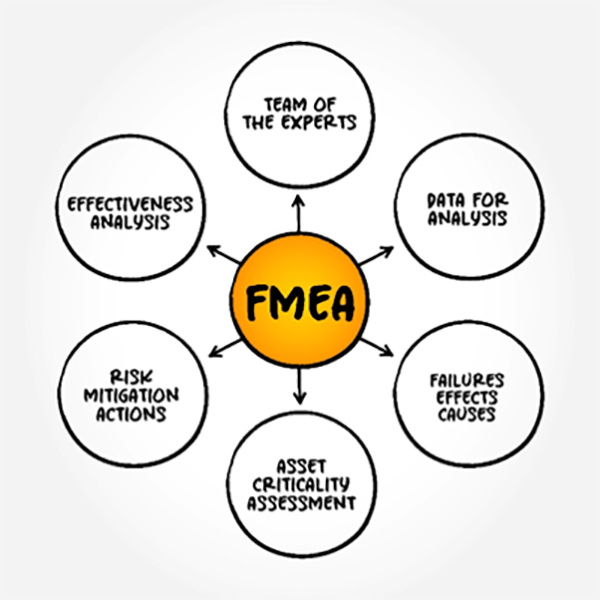

- Outline the role of root cause analysis and failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA) as part of the investigation of the causes of medication errors.

Flora Harp, PharmD, is an Editor at TRC Healthcare. She obtained her PharmD degree from Wayne State University. She then completed a community practice residency at CVS Health, focused on corporate clinical support. After completing her residency, Flora went on to hold different roles at CVS Health, where she supported various clinical services and programs. She also spent time as a formulary management pharmacist for Medicare Part D plans at Prime Therapeutics. Prior to joining TRC Healthcare in 2016, Flora was a Clinical Services Manager at Thrifty White Pharmacy, where she oversaw various clinical programs including immunizations, rapid diagnostic testing, medication therapy management, and testing of innovative clinical service models in collaboration with payers, accountable care organizations, manufacturers, and others. She also helped support the early stages of seeking URAC accreditation for their growing specialty pharmacy business.

Contributing faculty, Flora Harp, PharmD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationship with any product manufacturer or service provider mentioned.

Supported browsers for Windows include Microsoft Internet Explorer 9.0 and up, Mozilla Firefox 3.0 and up, Opera 9.0 and up, and Google Chrome. Supported browsers for Macintosh include Safari, Mozilla Firefox 3.0 and up, Opera 9.0 and up, and Google Chrome. Other operating systems and browsers that include complete implementations of ECMAScript edition 3 and CSS 2.0 may work, but are not supported. Supported browsers must utilize the TLS encryption protocol v1.1 or v1.2 in order to connect to pages that require a secured HTTPS connection. TLS v1.0 is not supported.

The role of implicit biases on healthcare outcomes has become a concern, as there is some evidence that implicit biases contribute to health disparities, professionals' attitudes toward and interactions with patients, quality of care, diagnoses, and treatment decisions. This may produce differences in help-seeking, diagnoses, and ultimately treatments and interventions. Implicit biases may also unwittingly produce professional behaviors, attitudes, and interactions that reduce patients' trust and comfort with their provider, leading to earlier termination of visits and/or reduced adherence and follow-up. Disadvantaged groups are marginalized in the healthcare system and vulnerable on multiple levels; health professionals' implicit biases can further exacerbate these existing disadvantages.

Interventions or strategies designed to reduce implicit bias may be categorized as change-based or control-based. Change-based interventions focus on reducing or changing cognitive associations underlying implicit biases. These interventions might include challenging stereotypes. Conversely, control-based interventions involve reducing the effects of the implicit bias on the individual's behaviors. These strategies include increasing awareness of biased thoughts and responses. The two types of interventions are not mutually exclusive and may be used synergistically.

#25-343: Medication Errors: Strategies for Prevention and Management

In the U.S., medication errors harm at least 1.3 million people every year and are responsible for causing at least one needless death every day [2]. In Canada, it is estimated that about 28,000 people die per year due to medical errors, most of which involve medications [3].

Fortunately, medication errors are preventable, and healthcare is in a constant state of evolution to improve patient safety.

The majority of medication errors occur because of weaknesses in our systems that allow mistakes to slip by, as opposed to individual negligence [4]. As humans, we are prone to making mistakes, so we need to have processes put in place that allow us to capture these "human errors" before they reach the patient. System problems can include issues with procedures or workflow, short-staffing, faulty or inadequate software, the layout and organization of the pharmacy, etc. Problems due to human error are usually best managed by system redesign and supporting the employee. System redesign can include changes in processes, procedures, and training that reduces the risk of errors.

Punishing healthcare professionals for making mistakes can get in the way of error prevention. Disciplinary action encourages a culture where medication errors and "near misses" are not reported. When this happens, it takes away the best mechanism for error prevention: analysis of errors and the processes that can be improved to increase prevention.

High-risk practices and situations are continuously being identified by organizations like the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), ISMP Canada, and The Joint Commission. Annual publication of the National Patient Safety Goals (NPSG) by The Joint Commission provides guidance to improve patient safety. From this information, policies can be created, raising awareness and facilitating practice changes for healthcare professionals.

An adverse drug event is defined as "an injury from a medicine or from the lack of an intended medicine" [6]. Risk factors for adverse drug events include a patient's age, gender, how many medications the patient takes, and concomitant disease states [7].

Some adverse drug events are adverse reactions. These are not always preventable if the drug was prescribed, dispensed, and administered appropriately. For example, a situation in which a patient on the correct drug, at the correct dose, and for the correct indication experiences an allergic rash when no previous drug allergy was known would be considered an unpreventable adverse drug event.

But some adverse drug events are the result of medication errors. In other words, the injury could have been prevented with some safety checks. An example of this would be if a hospitalized patient known to be allergic to a medication is incorrectly administered the drug they are allergic to because the allergy was never documented in the patient's chart.

Medication errors are defined as "any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the medication is in the control of the healthcare professional, patient, or consumer" [11]. Such events may be related to all aspects of medication use [12]:

Administration, education, monitoring, use

Compounding, dispensing, distribution

Prescribing, order communication

Product labeling, packaging, nomenclature

Professional practice, healthcare products, procedures, systems

ISMP defines a near miss or close call as an event, situation, or error that occurred but did not reach the patient [13]. Analysis of near misses can help change systems before errors occur and should be part of quality reviews, reporting, etc.

It's important to define exactly what a medication error is and what a medication error isn't. This allows medication errors to be identified by healthcare providers, patients, administrators, and national organizations that track errors, such as ISMP. Once a medication error is identified, strategies can be developed to prevent it from happening again.

The first step in preventing errors is gathering information on what leads to errors. Recognizing that a medication error has occurred is the beginning of the quality improvement cycle. Finding out why it occurred is the next step.

Errors can occur at any step in the medication use process, including prescribing, order communication, preparation (e.g., labeling, repackaging, compounding, dispensing), administration, or monitoring.

Examples of some common causes of errors include:

Errors in patient administration and use due to a lack of understanding

Misinterpretation of product names, directions, abbreviations, or writing

Poor communication

Poor procedures or techniques

Many medication errors occur during the prescribing step [15]. Potential causes of prescribing errors include lack of knowledge about the patient, such as other medications they are taking or their lab values, or insufficient drug knowledge [16].

Create a relationship with the prescribers you work with on a regular basis to help improve communication. Let them know what services you can provide. This will encourage them to come to you with medication questions. Find ways to become involved in their practice. For example, give in-services at their clinics/offices about new medications or studies, provide information sheets they can post in staff rooms or give to their patients, etc.

A study that looked at nearly 10,000 prescriptions written by community-based prescribers over a 15-month period found that one in four prescriptions contained at least one prescribing error, even without counting errors due to poor handwriting (illegibility) [18]. Among drug categories, antibiotics had the most prescribing errors, followed by cholesterol medications, narcotic analgesics, and blood pressure drugs [19].

There is often information missing from prescriptions [20]. One way to prevent this from happening is for prescribers to be provided with prompts on exactly what information is necessary. For those using electronic health records, prescribers can be stopped from sending prescriptions until all necessary fields are complete. Templates for "ideal" or usual prescriptions can also be created by gathering data on common prescription errors and then creating an electronic template or a prescription pad with prompts for the common parts of a prescription, with name, strength, dose, frequency, etc. [20]. These templates can also include a prompt for the medication's indication, further increasing communication between the prescriber and pharmacist. Other common errors include incorrect dose, strength, frequency, abbreviations, and directions for use [19].

Many solutions to prescribing errors may require changing long-standing habits, which can be difficult. Here are some recommendations for written prescriptions [20,21]:

Prescriptions must be legible. Verbal orders must be minimized, or the contents confirmed by reading back the Rx to the person giving the order.

Prescriptions should include a brief indication. This adds an extra safety step, allowing pharmacists to check doses more accurately and counsel patients accordingly.

Prescriptions should be written using the metric system.

Prescriptions should include relevant patient information (age, weight, etc.). This is especially important for accurate pediatric and geriatric dosing.

Prescriptions should include leading zeros used before a decimal quantity less than one. Trailing zeros should NOT be used after a decimal.

Prescriptions should contain specific directions for use, not "use as directed."

Prescriptions should not contain error-prone or confusing abbreviations.

E-prescribing helps to reduce some types of prescribing errors. Prior to electronic prescribing, one pediatric ambulatory clinic found 77.4% of prescriptions contained at least one error compared with 4.8% after the institution of electronic prescribing. Before electronic prescribing, the most common errors were attributed to missing essential information (73.3%) or illegibility (12.3%). After the start of electronic prescribing, the rate of missing information declined to 1.4% and illegibility was eliminated [22].

In 2000, ISMP called for the elimination of handwritten prescriptions in order to reduce errors from illegible and misinterpreted prescriptions [23]. In 2006, the Institute of Medicine recommended that e-prescribing be put into place for all prescriptions by 2010. In Canada, the Canadian Medical Association (CMA) and the Canadian Pharmaceutical Association (CPhA) both called for e-prescribing to be in place by 2015 in order to improve patient care and safety [24].

Rates of e-prescribing remain high in the United States, due in part to the fact that most states have legislation in place that mandates the use of e-prescribing for all controlled substances, a subset of controlled substances (typically opioids), or all prescriptions [24]. Additionally, prescribing of controlled substances for patients with a Medicare Part D or Medicare Advantage prescription drug plan must be done electronically [25]. Whether e-prescribing is mandated by state or federal law, be aware of the exceptions in place that allow for certain prescribers or particular prescriptions to be exempt from the e-prescribing requirement.

In 2024, 1.34 million prescribers in the United States used e-prescribing (a 3.9% increase from 2023) and e-prescriber enablement of e-prescribing for controlled substances (EPCS) was up to almost 84% of prescribers [27]. To improve e-prescribing rates in Canada, a national e-prescribing service was launched in 2017 [26].

There are several strategies prescribers can employ to reduce electronic prescribing errors:

Always verify birth date of the patient.

Check for alternate spellings of patient names, and hyphenated names.

Use photographs of patients if your system uses this technology.

Be alert for similar spellings of drug names (e.g., use "TALL man" lettering to help differentiate similar-looking drug names, such as hydrOXYzine and hydrALAZINE).

Watch for different salt forms (e.g., use brand and generic drug name combinations to help differentiate, such as metoprolol TARTRATE [Lopressor] and metoprolol SUCCINATE [Toprol XL]).

Watch for different formulations (immediate-release and extended-release).

Make sure discontinued drugs are removed from the pharmacy automatic refill program.

Don't assume default values are accurate. Double-check values and report discrepancies; keep in mind that not all defaults apply to your specific patient.

Don't split sig between the sig field and notes field. If necessary, it may be better to use "As directed in notes section" in the sig field and then add specific directions to the notes field. For example, avoid putting "once daily" in the sig field and then tapering directions in the notes field. These notes often get missed.

Use the notes field to add complicated sigs such as steroid tapers that won't fit into your sig field.

A majority of the legal claims against pharmacists involve dispensing errors, particularly due to the wrong drug or dose/strength being dispensed [18]. Most dispensing errors can be avoided if preventive measures are in place. Some of these measures could include avoiding use of dangerous abbreviations, being alert to look-alike/sound-alike drugs, checking for allergies, reading back phone orders, and providing proper patient counseling [18]. Dispensing errors in hospitals may occur when a member of the patient care team performs an automated dispensing cabinet (ADC) override and withdraws a medication from the ADC before pharmacist review of the order. This practice bypasses the safety net of pharmacist review and should be minimized to cases where it's absolutely needed, such as if delay would harm the patient or the patient experiences a sudden change in clinical status [29,30].

Here are examples of wrong drug mix-ups that have reached patients. Notice how these examples include similar looking or sounding medications that come in the same strengths [18]:

Abilify (aripiprazole) 10 mg dispensed instead of Aricept (donepezil) 10 mg

Clozapine 50 mg dispensed instead of chlorthalidone 50 mg

Duloxetine 30 mg or 60 mg instead of dexlansoprazole 30 mg or 60 mg

Gabapentin 600 mg dispensed instead of ibuprofen 800 mg

Keflex (cephalexin) 500 mg dispensed instead of Keppra (levetiracetam) 500 mg

Lamotrigine 200 mg dispensed instead of labetalol 200 mg

Levofloxacin 750 mg dispensed instead of levetiracetam 750 mg

Methotrexate 2.5 mg dispensed instead of metolazone 2.5 mg

Morphine ER 200 mg dispensed instead of ibuprofen 200 mg

Examples of wrong strength errors that have reached patients include [18]:

Amitriptyline 100 mg dispensed instead of 10 mg

Aripiprazole 20 mg dispensed instead of 2 mg

Methotrexate 2.5 mg dispensed once daily instead of once weekly

Morphine 100 mg/5 mL dispensed instead of the 20 mg/5 mL strength

Simvastatin 80 mg dispensed instead of 40 mg

Tacrolimus 5 mg dispensed instead of 0.5 mg

Warfarin 5 mg dispensed instead of 2 mg

The most common factors leading to wrong drug dispensing errors that resulted in legal claims include [18]:

Failure to prevent sound-alike drug errors (36%)

Failure to check drug against label and actual prescription (32%)

Failure to prevent look-alike drug errors (11.5%)

Note that confused drug errors (those involving sound-alike and look-alike errors) made up the most common type of wrong drug dispensing error claims.

Be aware of best practices to prevent dispensing errors. Adjust your practice so these activities are second nature; make them a habit when you are dispensing prescriptions [13]:

Pharmacists should not dispense an unfamiliar drug until performing appropriate research regarding its uses, contraindications, and hazards.

Clarify with the patient and/or prescriber the patient's clinical history and diagnosis to ensure appropriate use of the prescribed drug.

Patient profiles should be current and contain enough information for pharmacists to assess appropriateness of medication therapy. Make notes and add dated information to help with future patient interactions and prescriptions. This helps provide clear information to all staff for future encounters.

Follow all pharmacy protocols and don't take shortcuts when entering a drug order into the computer system. Use only approved sigs.

Double-check all auto-populated information from an electronic prescription since information may not be transcribed completely or accurately.

Make sure Rx directions are clear, correct, and complete; include all directions and information for the patient from the sig and e-Rx notes on the label, such as indications, whether a drug should be used as needed ("PRN"), or durations of therapy (antibiotic courses, etc.).

Don't automatically override any alerts without appropriate verification.

Pharmacy technicians should alert the pharmacist (who may need to contact the prescriber) regarding any questionable prescription or alerts prompted by the dispensing system.

Ensure all prescriptions are checked prior to dispensing. Verify each prescription against the original order.

Pharmacists should counsel patients when dispensing medications. This is an important safety check for correct dispensing and ensuring patient comprehension. Ask open-ended questions of the patient to engage them in conversation. Discourage having the pharmacy technician simply ask patients, "Do you have any questions for the pharmacist?" Patients often don't have or can't think of questions on the spot. Asking the patient open-ended questions may help uncover any problems or issues.

Work areas and workflow should be well designed to help prevent errors, such as adequate lighting, low noise, few distractions, etc.

Drugs should be organized or otherwise differentiated to reduce confusion between similar names, labels, or strengths. Consider using color-coded baskets, shelf dividers, signs, notes, etc., to draw attention to high-risk medications and commonly confused drugs.

Pharmacies should have and follow dispensing policies and procedures. This creates a standard of practice for all staff to follow. These should be reviewed if a near miss or error occurs as it provides an opportunity to revise procedures, when appropriate, to prevent future errors.

The avoidance of prescribing, and especially dispensing, drugs a patient is allergic to is very important. The rate of emergency room visits for anaphylaxis has increased over the years, especially among young people [31]. Anaphylaxis is a serious allergic reaction that is rapid in onset and can progress to death. Food triggers, such as peanuts, shellfish, and eggs, are common. Be cautious of excipients in medications when patients have allergies. For example, if a patient has an allergy to soy, you may need to analyze products carefully to ensure they are soy-free. Medications such as beta-lactam antibiotics and NSAIDs are also often implicated in anaphylactic reactions. Injectable epinephrine is standard treatment in anaphylaxis management. Help patients at risk for anaphylaxis get an epinephrine auto-injector [21].

Generally, errors happen because of weak points or flaws in the medication use system. This system includes every step in the medication use process from writing the prescription, dispensing the medication, to administering the medication. Many factors along the way can contribute to the failure of the medication use system and result in medication errors. Organizations like ISMP, Health Canada, FDA, and The Joint Commission collect data on medication errors, analyze the data to uncover the causes of errors, and then alert pharmacists and prescribers so that errors can be prevented.

Certain behaviors can increase the risk of errors. These behaviors can be intentional as part of the person's decision-making process, or unintentional and inadvertently committed without the person's awareness. Good medication use processes can help catch human errors because most of these processes involve at least two checks. It usually takes more than one human error to cause a medication error.

Three different types of human behaviors lead to errors:

Human error

At-risk behaviors

Reckless conduct

Human error involves unintentional and unpredictable behavior that causes or can cause errors. We often refer to this as an inadvertent mistake, slip, or lapse in concentration.

Example: A pharmacy tech inadvertently clicks on fentanyl 75 mcg instead of fentanyl 25 mcg while inputting a prescription and the pharmacist fails to notice this discrepancy when checking the prescription.

At-risk behavior is a set of choices made by workers that increase risk and the risk is mistakenly believed to be justified. It often occurs as workers try to do more with less by taking shortcuts, violating policies, and drifting away from behaviors they once knew as safe.

Example: The pharmacy is very busy, so a pharmacy tech uses her best guess on an illegible prescription instead of verifying it prior to order entry, and the pharmacist doesn't double-check with the prescriber since it is most likely correct.

Reckless conduct occurs when the worker perceives the risk they are taking and understands that the risk they are taking is substantial. This is a conscious disregard of a visible, significant risk.

Example: A pharmacist is behind with verifying prescriptions and, to save time, doesn't double-check the technician's calculations used to prepare compounded medications that day.

One interesting area of investigation involves the effects of confirmation bias. Humans have a tendency to inadvertently seek confirmation of our beliefs. This means we see what we THINK we should see instead of what is actually in front of us. This phenomenon most commonly occurs when a pharmacist's or pharmacy technician's attention is diverted and the mind inadvertently "fills in the gaps." Confirmation bias is involuntary and usually unnoticed, so it is important to consistently use and optimize alerts, flags, minimize distractions and diversions, and maintain proper workload.

Some steps can be taken to help avoid confirmation bias:

Make high-risk or error-prone drugs highly conspicuous. This can be done with bright colors, "TALL man" lettering , and unusual shapes.

Don't over-depend on technology. Don't assume that automated systems will pick up all problems. Use the verification steps in processing a prescription to make sure the prescription is truly error-free.

Limit interruptions and distractions, and manage workload. Multitasking can lead to a loss of focus and carelessness.

Pay attention to your limits. Everyone is different. Know what impairs your ability to concentrate, such as interruptions, working too fast, illness, fatigue, or medication use; and manage appropriately.

Addressing human behaviors that lead to errors may be best done in a "Just Culture" environment. This involves a thorough and appropriate evaluation of medication errors and taking actions to prevent the circumstances leading to errors. "Just Culture" is an accountability model that requires and motivates people to speak up and take action in the interest of safety. A culture is "just" because it is one that has a clear, fair, and transparent process for evaluating errors and separating blameworthy from blameless acts. It evaluates and determines a course of action based on the circumstances leading to the error, not the outcome of the error itself [28,29]. Many pharmacies and organizations adopt the Just Culture model for dealing with errors.

In a Just Culture environment, the outcome is not taken into consideration when evaluating and addressing the behavior that led to the error. It is the quality of the behavior itself that determines the action used to address it. The following actions are appropriate when addressing an error in a Just Culture environment:

Human error: These are best managed by system redesign such as improvements in processes, procedures, and training that reduces the repetition of errors.

Example: The use of "TALL man" lettering for look-alike drugs.

At-risk behavior: This is best managed by removing barriers to safe behavior, coaching, and removing incentives and rewards for unsafe behaviors.

Example: Updating software so technicians can't automatically override severe drug interaction alerts before the pharmacist can evaluate them. And requiring verification from pharmacists to proceed past a severe drug interaction warning, perhaps by typing in a reason or action taken.

Reckless conduct: This is managed by holding the individual accountable and having zero tolerance for such behavior.

Example: Disciplining a pharmacist who chooses to not double-check a technician's calculations used to prepare a parenteral nutrition (PN) solution, whether or not it led to an error.

Abbreviations are a big problem in the healthcare setting, contributing to many medication errors. Abbreviations can be misinterpreted, misunderstood, and confusing. Combining abbreviations with handwriting that is difficult to decipher may cause even more confusion. The use of abbreviations puts patient safety at risk. Abbreviations may save time initially, but they can actually end up costing more time due to ambiguity.

Simply avoiding abbreviations goes a long way toward preventing medication errors and is recommended by ISMP. For The Joint Commission accreditation, hospitals are required to have a list of prohibited abbreviations, a so-called "Do Not Use" list [30]. These abbreviations must not be used in chart orders, progress notes, etc. It's important to avoid these abbreviations in the community pharmacy too. Some notations and abbreviations that are particularly dangerous include: U and IU for units; QD for once daily; QOD for every other day; trailing zeros on doses; lack of a leading zero for doses less than one; and the drug abbreviations MS, MSO4, and MgSO4, which can be interpreted as either morphine sulfate or magnesium sulfate [34].

Table 1 contains examples of abbreviations that can compromise patient safety, along with their potentially harmful consequences, and recommendations for clarification [34,36].

DANGEROUS ABBREVIATIONS

| Abbreviation | Intended Meaning | Potential Error | Recommendation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Joint Commission's "Do Not Use" List | ||||||||

| U, u | Unit | Mistaken for "0" (zero), the number "4" four, or "cc" | Write "unit" | |||||

| IU | International unit | Mistaken for IV (intravenous) or the number "10" (ten) | Write "international unit" | |||||

| qd, QD, q.d., Q.D. | Daily | Mistaken as every other day (qod) or four times daily (qid) | Write "daily" | |||||

| qod, QOD, q.o.d., Q.O.D. | Every other day | Mistaken as daily (qd) or four times daily (qid) | Write "every other day" | |||||

| Trailing zero (X.0 mg) | X mg | Decimal point is missed | Write X mg | |||||

| Lack of leading zero (.X mg) | 0.X mg | Decimal point is missed | Write 0.X mg | |||||

| MS | Morphine sulfate or magnesium sulfate | Confused for the opposite intended | Write "morphine sulfate" | |||||

| MSO4 | Morphine sulfate | Confused for magnesium sulfate | Write "morphine sulfate" | |||||

| MgSO4 | Magnesium sulfate | Confused for morphine sulfate | Write "magnesium sulfate" | |||||

| Examples of Other Abbreviations to Avoid | ||||||||

| µg | Microgram | Mistaken as milligram (mg) | Use mcg | |||||

| > and < | More than and less than |

| Use "more than" or "less than" | |||||

| @ | At | Mistaken as the number "2" | Use "at" | |||||

| cc | Cubic centimeters | Misread as "u" (units) | Use "mL" | |||||

| Apothecary units (e.g., minims, grains) | Varies | Confused with metric units; unfamiliar to some healthcare professionals | Use metric system | |||||

| APAP | Acetaminophen | Not recognized as acetaminophen | Use complete drug name | |||||

| CPZ | Compazine (prochlorperazine) | Mistaken as chlorpromazine | Use complete drug name | |||||

| HCT | Hydrocortisone | Mistaken as hydroCHLOROthiazide | Use complete drug name | |||||

| HCTZ | HydroCHLOROthiazide | Mistaken as hydrocortisone | Use complete drug name | |||||

| MTX | Methotrexate | Mistaken as mitoXANTRONE | Use complete drug name | |||||

| PTU | Propylthiouracil | Mistaken as Purinethol (mercaptopurine) | Use complete drug name | |||||

| SSI | Sliding scale insulin | Mistaken as Strong Solution of Iodine (Lugol's) | Use "sliding scale (insulin)" | |||||

| SSRI | Sliding scale regular insulin | Mistaken as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | Spell out "sliding scale (insulin)" | |||||

| TAC | Triamcinolone, tacrolimus |

|

| |||||

| / (slash mark) | Separates two doses | Mistaken as the number 1 (e.g., 25 units/10 units misread as 25 units and 110 units) | Use "and" rather than a slash mark to separate doses | |||||

| Qhs | Nightly at bedtime | Mistaken as qhr (every hour) | Use QHS or qhs for bedtime | |||||

| TIW or tiw | Three times a week | Mistaken as 3 times a day or twice in a week | Use 3 times weekly | |||||

| BIW or biw | Two times a week | Mistaken as 2 times a day | Use 2 times weekly | |||||

| SC, SQ, sq, or sub q | Subcutaneous(ly) |

| Use SUBQ (all UPPERCASE letters, without spaces or periods between letters), or subcutaneous(ly) | |||||

| D/C | Discharge or discontinue | Premature discontinuation of medications if D/C (intended to mean discharge) on a medication list has been misinterpreted as discontinued | Use discharge and discontinue or stop | |||||

| AD, AS, AU | Right ear, left ear, each ear | Mistaken as OD, OS, OU (right eye, left eye, each eye) | Use right ear, left ear, each ear | |||||

| OD, OS, OU | Right eye, left eye, each eye | Mistaken as AD, AS, AU (right ear, left ear, each ear) | Use right eye, left eye, each eye | |||||

| UD | As directed (ut dictum) | Mistaken as unit dose (e.g., an order for "dilTIAZem infusion UD" mistakenly administered as a unit [bolus] dose) | Use as directed | |||||

| q 6PM, etc. | Every evening | Mistaken as every 6 hours | Use daily at 6 PM or 6 PM daily | |||||

| IN | Intranasal | Mistaken as IM or IV | Use intranasal | |||||

| IT | Intrathecal | Mistaken as intratracheal, intratumor, intratympanic, or inhalation therapy | Use intrathecal | |||||

| IJ | Injection | Mistaken as IV or intrajugular | Use injection | |||||

A list of "Do Not Use" abbreviations is also available on The Joint Commission's website [34]. ISMP also has a list of "Error-Prone Abbreviations" on their website [35].

Drug products present plenty of opportunities for errors. From drug names that look alike when they're handwritten or sound alike when spoken, to drug packaging that is strikingly similar between very different products. It's of paramount importance to be aware of the potential for mistakes as well as safeguards that can be used to prevent them.

Products that look alike or sound alike are one of the most common causes of medication errors [33]. ISMP has even developed a "List of Confused Drug Names" to increase awareness of commonly confused medication names [34]. Mix-ups with confused drug names can occur at the time of prescribing, order entry, dispensing, administration, or monitoring [36]. Sometimes these errors occur when patients relay their medication lists verbally to a specialist or when admitted to the hospital.

Other errors occur when packages are similar in appearance. This usually happens when there are several concentrations of the same medication. For example, heparin has been a high-alert medication for decades due in part to dosing confusion stemming from similar looking container labels for the different strengths. There are repeated reports of miscalculations and mix-ups that have resulted in patient harm and deaths. Package labeling was updated in 2013 to include both the units of heparin per mL, and the total units of heparin in the container, to make it easier to differentiate between the different concentrations [35].

Some names are accidents waiting to happen, especially with drugs that come in similar strengths. One example is Keppra, Kaletra, and Keflex. Confusion is especially likely between Keflex and Keppra because both are available as 250 mg and 500 mg strengths. Metformin and metronidazole can also be confused and they both come in a 500 mg strength. Another example is risperidone (Risperdal) and ropinirole (Requip) which are available in similar strengths including 0.25 mg, 0.5 mg, 1 mg, 2 mg, 3 mg, and 4 mg.

When looking for solutions to medication name mix-ups, it is important to consider the contributing factors. These factors can be divided into the following categories [38]:

Individual

Environmental

Technological

Unique

Individual factors include illegible handwriting and lack of knowledge. Electronic health records and e-prescribing have helped to eliminate some of the challenges we've seen with understanding written prescriptions. For handwritten prescriptions, independent double checks can also help reduce individual human errors [36].

Environmental factors, such as drug storage, workflows, and dispensary organization, can affect error rates. Pharmacies should be designed to have enough space for safe and efficient workflows [36].

Technology can be useful in reducing some types of errors (e.g., illegible handwriting); however, other functions can be prone to errors when not used properly. Pharmacies should be wary of using functions in their systems such as "copy" for prescriptions, as incorrect information often gets copied to the new prescription [36].

Other, unique factors may apply to individual pairs of products. These include similar names, doses, indications, formulations, etc. Check to see if you can add alerts in your computer system for common mix-ups. You can also look at unique labeling and storage (e.g., color-coding, auxiliary stickers) that can be used in your own pharmacy to distinguish between products [36].

In an attempt to distinguish among look-alike names, "TALL man" letters were developed. Drug names are written with different capitalized letters inserted into similar drug names (e.g., glipiZIDE and glyBURIDE). ISMP has a list of look-alike names with recommendations for "TALL man" lettering [39]. "TALL man" lettering is recommended whenever these medication names are used in an electronic health record, pharmacy computer system, e-prescribing system, etc. If you don't see "TALL man" lettering in your electronic systems, look at working with your computer support team to have it added.

To add to the confusion, unfortunately, some medications still have two brand names (e.g., Zyban and Wellbutrin are both brand names for bupropion), or you may find people who are familiar with a different brand name from another country (e.g., Flomax [tamsulosin] is the name for an NSAID in Italy) [40].

There's a lot that can be done to prevent mix-ups with look-alike/sound-alike drug names. Make sure that prescriptions are written clearly and avoid abbreviations. Include both brand and generic names to provide additional clarification. Repeat drug names back to the prescriber when taking a verbal order. It's also helpful if prescribers make sure patients are aware of the reason a medication has been prescribed and include the indication for use on the prescription. For instance, if you receive a prescription for atorvastatin with a sig that says "1TPOHS for cholesterol," you should type up the directions as, "Take 1 tablet by mouth at bedtime for cholesterol." Including the indication will remind the patient what the medication is for, which can be especially important when taking multiple meds. Also think of this as another safety check in the dispensing process. For example, digoxin, a heart medication, can sound similar to levothyroxine, a thyroid medication. So an Rx for digoxin with the sig, "Take 1 tablet by mouth daily for thyroid" is a red flag that something is off.

Pharmacists can double-check with patients about their meds during counseling. Asking open-ended questions such as what drug the patient is expecting, what is the indication, and how the prescriber said to use the drug can help catch errors. Use the patient's responses to double-check what's being dispensed. Make sure the indication matches the drug.

Similar packaging and storage location can also contribute to errors. Look-alike products should not be placed side by side. This applies to any location where medications might be stocked or stored, from pharmacy shelves to other medication storage areas. Use shelf tags, separate look-alike drugs on pharmacy shelves, put alerts in your computer system, highlight bottles with stickers, etc. Also, when pulling medications from the shelf, look closely at NDC (or DIN in Canada) numbers. They can be very similar. Checking these numbers is another way to help prevent medication errors with look-alike/sound-alike meds.

Suffixes at the end of drug names such as CD, SR, and XL can increase the risk of errors. There is no standard meaning to suffixes, and the suffixes don't tell you how fast the medication is released or how often it is dosed. Errors that result from the use of suffixes may happen because of confusion about the suffix, not knowing what the suffix means, and lack of standardized meanings across suffixes. This can lead to product mix-ups, prescriptions written with incorrect dosing intervals or frequencies, omission of a suffix, incorrect suffix, etc. There are recommendations that promote the safe use of suffixes. Safety recommendations regarding suffixes include [42]:

Regardless of the prescription format (written, oral, electronic, etc.), prescribers should always indicate the complete proprietary and/or generic drug name, including the suffix when applicable.

Pharmacists should call prescribers to clarify prescriptions where the presence or absence of a suffix doesn't agree with the prescribed dosing schedule.

Patients should be proactively educated about the use and meaning of drug name suffixes.

Medication errors, including near misses, associated with the use of drug-name suffixes should be reported.

Drug products that contain suffixes in the name should be evaluated to determine the potential for errors in all stages of the medication use process.

One example of an area of confusion with drug name suffixes is with bupropion products. Wellbutrin SR and Wellbutrin XL are both formulations of bupropion, expected to have similar efficacy for treating depression. The difference between these products is the usual dosing frequency. Wellbutrin XL is given once a day and Wellbutrin SR is given twice a day. For example, Wellbutrin XL 300 mg once a day is equivalent (but not interchangeable) to Wellbutrin SR 150 mg twice a day. But, do not assume that a prescription written for Wellbutrin once a day is the XL version if it is missing the suffix or the suffix is illegible. The pharmacist should always double-check these with the prescriber.

There's also potential for mix-ups between the Depakote ER and the original Depakote tablets (which has no suffix). Depakote ER comes in a 250 mg and a 500 mg tablet and is approved for preventing both migraines and seizures. The "ER" stands for extended-release. The original Depakote is a delayed-release tablet (but has no suffix). It releases the drug over eight to 12 hours and is usually given two to three times a day. Depakote ER once daily works just as well as original Depakote two or three times a day for seizures.

Be alert for products you know have a suffix and the potential for missing information on a prescription. Always make sure the drug name, dosage form, strength, and dosing frequency match. Call the prescriber for clarification if there is any uncertainty.

Over-the-counter (OTC) brand-name extensions can cause confusion and patient harm. To capitalize on name recognition and product loyalty, the manufacturer of a commonly recognized brand might market additional products using that same brand name, but with different ingredients and possibly for a different indication.

For example, Advil PM contains both ibuprofen and diphenhydramine. Patients may not realize that a product with Advil in the name would contain the same ingredient as Benadryl (diphenhydramine). If a patient also takes Benadryl at the same time for cold symptoms, they may end up taking too much diphenhydramine. Too much diphenhydramine can cause excessive drowsiness, dizziness, headache, etc. Checking the active ingredients on the label and encouraging patients to do so is very important.

When discussing an OTC product, specify ingredient instead of brand name to prevent confusion. Ask patients about their intended use of OTC products. Pharmacies can stock OTC products by therapeutic category and use shelf alerts to warn customers of product changes.

Many medication error reports submitted to ISMP are related to product or device problems. A number of medication devices have been identified as potentially prone to medication error. These include medication delivery pens and inhaler devices. Teaching the proper use of devices like these is a great opportunity for patient counseling.

Medication delivery devices used in the hospital are also at risk for user error. For example, a nurse was changing the concentration of a medication being infused through a pump. She misunderstood the default settings and accepted a bolus concentration as the final dose. The patient received a three-fold overdose [43]. Understanding how to use a medication delivery device is extremely important for personnel who will be administering meds. Pharmacy teams can help educate others, such as nurses, on how to use these devices to help prevent errors.

Brand-name products often have different ingredients in different countries. For example, Dilacor, a diltiazem product in the U.S., is a brand name for digoxin in Serbia. Dilacor is also a brand name for verapamil in Brazil and the calcium channel blocker, barnidipine, in Argentina [43].

Another example is Vantin. This product is naproxen in Mexico was the brand-name for cefpodoxime in the U.S. [48,49]. Other times, foreign drug products can have look-alike or sound-like names, such as Zertalin (azithromycin in Mexico) and sertraline [50]. Because foreign products are less familiar, the potential for mix-ups is heightened.

Tell patients who travel abroad to carry enough of their meds and a list of their drugs by BOTH generic and brand name. Warn patients who are getting drugs abroad to beware. Although medications may seem less expensive, they may not be getting the intended medication. To find out the ingredients of a foreign drug, check with a drug information center (some colleges or pharmacy have one) or call 800-222-1222 to contact your regional poison control center.

When traveling with medications, patients should be careful not to expose them to extreme temperatures (e.g., in checked baggage or the glove compartment of a car). Having medications in their original labeled prescription containers helps to identify them during security checks and ensures relevant information is readily available if needed.

Deviation from the standard medication dispensing or administration procedures can result in medication errors. For example, skipping a final check can be a cause of dispensing errors. Errors can also happen when a prescription is filled from a label rather than checked against the original prescription [46].

"At-risk" behaviors can compromise patient safety. It's human nature to look for and use shortcuts, but in healthcare the results can have serious consequences. As competency is built, pharmacists or pharmacy technicians may rely on shortcuts and at-risk behaviors for short-term gains, such as increasing productivity. In contrast to the immediate benefits of getting work done faster, the risk of patient harm may seem remote. And use of at-risk behaviors may influence coworkers and become ingrained in the culture, until the behaviors become the rule instead of the exception [50].

At-risk behaviors frequently result from workarounds of existing workflow systems. Examples of at-risk behaviors include [50]:

Not fully reading medication labels before dispensing, administering, or restocking them.

Reluctance to ask for help or seek clarification on questionable prescriptions.

Using or dispensing a medication without complete knowledge of the indications, dosing, and side effects.

Not double-checking and following procedures for "high-alert" medications (blood thinners, opioids, etc.) before dispensing or administering them (more on high-alert meds later).

Not communicating or reviewing important information, such as patient allergies, comorbidities, weight, date of birth, drug interactions, etc.

Not including the medication's indication or "as needed" within the Rx directions when the indication or "PRN" is included in the Rx sig, because the extra information is considered to be unnecessary. For example, if a hydrocodone/acetaminophen Rx says "1 tablet PO TID PRN" but you leave off "as needed," the patient may take the med around the clock increasing the risk of side effects or opioid misuse.

To reduce these behaviors, pharmacies can eliminate organizational tolerance of risk, determine the system-based reasons for risk-taking behaviors, increase awareness of at-risk behaviors, eliminate system-wide incentives for at-risk behaviors, and motivate through feedback and rewards. Essentially, organizations must not foster dangerous behaviors by ignoring or tolerating them, or by giving employees the impression that efficiency is valued over safety. Managers and pharmacists-in-charge can lead by example by demonstrating the proper way to perform activities in their day-to-day activities [50].

While some computer systems may be programmed to catch as many problems as possible, too many alerts can actually decrease their effectiveness. This is sometimes referred to as "alert fatigue" [47].

Be sure to always follow your pharmacy's policies and procedures when it comes to handling alerts. Work with your computer support team where possible to focus on the quality of alerts, while decreasing the quantity. Many systems allow alerts to be customized to suit your needs, depending on your pharmacy's policies. Some hospitals have created committees tasked with reviewing alerts, analyzing alerts that are overridden (resulting in errors), and approving any proposed "pop-ups" and alerts in electronic health records.

The key is knowing which alerts are important and which are not. Discontinued drugs cause many alerts, but most aren't serious. But be aware of medications that have long durations of action as their effects can last after discontinuation. Interactions with amiodarone, fluoxetine, and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs; e.g., phenelzine, tranylcypromine) can occur for two weeks or longer after the med is stopped. Be careful when cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme inhibitors or inducers are discontinued. These CYP enzyme inhibitors or inducers can increase or decrease the activity of some drugs (i.e., substrates). Any substrate that is continued after the discontinuation of CYP enzyme inhibitors or inducers may need a dose adjustment.

Drug class alerts can be inappropriate when the interaction is only relevant to specific drugs in the class. For example, not all statins interact with CYP3A4 inhibitors and not all macrolides interact with CYP3A4 substrates.

The inclusion of topical and ophthalmic formulations in drug interaction alerts can contribute to alert fatigue as many of these are not significant. But know that not all topical or ophthalmic formulations are exempt from drug interactions. For example, timolol (Timoptic, etc.) eye drops can worsen bradycardia (slow heart rate) when given with other drugs that slow cardiac conduction, like verapamil or digoxin, especially in patients with heart failure or who already have a slow heart rate. And CYP2D6 inhibitors, such as paroxetine, can significantly increase timolol blood levels, especially when patients are using timolol 0.5%. That's because one drop of 0.5% timolol in each eye is approximately equivalent to a 10 mg oral dose [48,49].

Serotonin syndrome alerts come up often, but it's important not to ignore these. Serotonin syndrome is a risk that is usually most concerning when multiple medications that increase serotonin activity in the brain are taken at the same time. Serotonin syndrome can lead to problems such as agitation, sweating, tremor, or more rarely, high body temperatures, muscle rigidity, and even death [50]. The riskiest combos should be avoided, such as MAOIs (selegiline, rasagiline, phenelzine, etc.) with other serotonergic drugs, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI; e.g., fluoxetine, paroxetine) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI; e.g., venlafaxine, duloxetine) [54]. Or serotonergic meds in combo with meds that have MAOI effects, such as isoniazid, linezolid, or metaxalone [51]. It's best to stay clear of combining tramadol with an SSRI or SNRI or opioids with serotonin effects (fentanyl, methadone, or meperidine) with other serotonergic meds [54,57,58]. And patients taking serotonergic meds should be discouraged from using OTCs or supplements with serotonin effects (dextromethorphan, L-tryptophan, etc.) [54].

QT interval prolongation alerts are often seen, and these can be serious because a long QT interval can lead to torsades de pointes, a dangerous heart rhythm disorder. Actual torsades de pointes is rare, but it can be life-threatening if it occurs. Watch for meds known to prolong the QT interval, such as methadone or amiodarone, particularly in patients at highest risk: women; older adults; and patients with heart failure, low heart rate, or low serum potassium or magnesium. Recommend an alternate drug for these high-risk patients. For more details on how to assess the risk for QT prolongation, check out our algorithm, Drug-Induced QT Prolongation: A Stepwise Approach (link provided in the Additional Resources section).

Continue to pay attention to the "big" drug interactions:

Potassium-sparing diuretics (e.g., spironolactone, eplerenone) with ACE inhibitors (lisinopril, enalapril, etc.) or ARBs (candesartan, losartan, etc.) – risk of high potassium (hyperkalemia)

Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX) with meds that can increase potassium levels (e.g., ACE inhibitors, ARBs, potassium-sparing diuretics) – risk of hyperkalemia

TMP/SMX with warfarin – risk of bleeding due to increased activity of warfarin

Clarithromycin with digoxin – risk of increased side effects of digoxin (heart rhythm disorders, confusion, etc.)

Clarithromycin with some statins – risk of increased side effects of the statin (muscle damage)

Combined hormonal oral contraceptives with certain enzyme inducers (carbamazepine, fosamprenavir, phenytoin, topiramate, etc.) – may decrease the efficacy of the oral contraceptives [54]

Also watch for interactions with narrow therapeutic index meds (e.g., transplant meds, seizure meds, warfarin) and high-alert meds. Work as a team within your pharmacy to create a list of the most concerning drug interactions that are most relevant for your setting so it can be easily referenced. However, your list will never be exhaustive due to new medications and new data, so do not let it give you a false sense of security.

The risk of error in any workplace can be increased by insufficient lighting, noise level, temperature, and the number of interruptions (telephone calls, questions from other staff members, etc.) and distractions (noisy workstation, phones ringing, chatter, TV monitors, etc.). To help reduce distractions, keep conversations short and work-related.

Pharmacies that have a counseling area and cash register away from the primary workspace may be more successful at improving this process.

Ineffective communication is a frequently cited cause of serious patient harm. Verbal prescription orders are not recommended, and it is suggested that they be reserved for urgent situations when written or electronic prescribing is not practical [56]. In the hospital setting, many institutions have created policies to prohibit any verbal orders. In pharmacies, the "verbal order read-back" is essential for all phone orders, verbal orders, and test results that must be taken verbally. This practice helps improve the effectiveness of communication, ensuring that important information is relayed in an accurate, complete, and unambiguous manner [57].

Verbal order read-back has been a National Patient Safety Goal in prior years and is a required practice of some healthcare organizations. Order read-back requires that the recipient first write down the complete order or enter the information into the computer system. The recipient of the information then reads back the order or test result to the individual who gave the order. The recipient must seek and receive confirmation from the individual who gave the order or test result that the information is correct [60].

Not enough can be said about the importance of patient education. Patients are the final link. If patients don't take their medications or take them incorrectly, then all the steps to help improve their health will be ineffective. Prescribers and pharmacists are important sources of information for patients. When counseling patients, be sure to use language that is simple and free from "medical jargon" that patients may not understand.

Pharmacies are encouraged to distribute "useful" written information to patients. This information is meant to help patients understand and properly use their medications and is often distributed through medication leaflets, commonly known as patient information sheets.

Patient information sheets should supply sufficient and specific information, including directions for use or adverse reactions. They should also be easy for patients to read and understand by using patient-friendly language and having proper print size and spacing [58].

Don't rely only on the written information patients get with their prescriptions. Use every interaction as an opportunity to ask questions and educate patients. Many patients quit taking their meds because they don't know why they need them, don't think they are helping, believe the drug is harmful, or they just plain forget. Patients who understand the benefits are more likely to take their meds appropriately.

Use a "teach back" approach. Have patients tell you how and why they are taking their meds. Tailoring drug regimens to the patient's lifestyle helps. For example, check for less expensive generics, meds with fewer doses, or a different side effect profile. When provided, put the diagnosis on the Rx label (this is required if the indication is included as part of the Rx sig), encourage use of a pillbox, give private counseling, and use refill reminder programs. Give patients positive feedback on progress, and encourage them to monitor their blood pressure, blood glucose, etc. Ask open ended questions, such as "What problems have you had with your medications?"

Consider inhaled medications as an example to illustrate the importance of pharmacists' counseling in preventing med errors. Patients have mistakenly swallowed tiotropium (Spiriva) capsules intended for inhalation. These inhalation powders look like oral capsules and come in blister packs. Swallowing them probably isn't harmful, but these patients don't get the respiratory benefit. It's also important for patients to follow manufacturer instructions regarding expiration dates of inhalers. Some expire relatively quickly after the protective packaging is removed, in as little as one month (e.g., Advair Diskus) or six weeks (e.g., Serevent Diskus). To make sure that patients get full benefits from their inhaled medications, it's always a good idea for pharmacists to review proper inhaler technique with them. Use test devices which can often be obtained from manufacturers.

There are many other drugs with unique administration instructions that make it extremely important for patients to receive counseling and education, such as insulin pens and other injectable drugs, nasal sprays, or even oral medications that must be taken a specific way (orally disintegrating tabs, sublingual tabs, etc.).

Certain medications are considered "high-alert," or "high-risk," when errors involving these medications can cause serious harm. This doesn't mean that high-risk meds are necessarily associated with more errors than other drugs; however, when errors do occur they can cause significant patient harm. For instance, antibiotics are one of the most common types of drugs involved with prescribing errors and adverse drug reactions [60,61]. Despite this fact, antibiotics aren't generally the drugs with the highest chance of actually causing serious harm to patients.

ISMP maintains a list of drugs and drug classes which have the highest risk of causing devastating consequences to patients if used inappropriately. These medications may need to have special safeguards in place, such as double checks, to reduce the risk of errors. Many pharmacies and institutions create their own list, usually based on the ISMP list plus any of their own near misses and reported errors. Lists of high-alert meds may include, but are not limited to [62,63]:

Antithrombotics used to thin the blood (enoxaparin, warfarin, etc.)

Chemotherapy drugs

Injectable electrolytes (potassium chloride, potassium phosphate, hypertonic sodium chloride, magnesium sulfate, etc.)

Insulin

Methotrexate

Opioids (fentanyl, hydrocodone, etc.)

Sedative agents, IV (lorazepam, midazolam, etc.)

Sulfonylurea hypoglycemics for diabetes (glipizide, glyburide, etc.)

Individual healthcare professionals and organizations alike are responsible for improving patient safety. Programs like the National Patient Safety Goals and other guidelines from groups like ISMP, The Joint Commission, and NCC MERP are updated periodically based on the real-world reports and experiences of healthcare workers, such as pharmacists and pharmacy technicians. It's important to stay current with these evolving requirements. We have touched on many of them already. Here's a rundown of ways to help prevent medication errors.

There are many things the individual can do to help prevent medication errors. Following the "five rights," staying current on education and training, using effective communication, engaging the patient, and looking for weaknesses in the system are just a few.

You may have heard of the "five rights" to help ensure patient safety. This list of rights is one way to remember to look for medication errors. In order to be error free, each drug administered must comply with these five items:

Right patient

Right drug

Right dose

Right time

Right route

Whenever one of these items is not right, a medication error (or near miss) has occurred.

Prescription labels need to show additional "rights," including right physician, right instructions, right number of refills, right quantity, or other legally required information. Some states now require a physical description of the medication on the prescription label, such as "blue scored tablet."

Education and training can reduce the risk of medication errors. Inadequate knowledge is frequently cited as a cause of medication errors. Continuing education for pharmacists and pharmacy technicians helps promote patient safety. Newly approved drugs are always arriving in the pharmacy. New drug interactions or side effects are uncovered on a regular basis. For pharmacy technicians, even basic pharmacology training is helpful for recognizing typical uses and doses of medications. For example, an order for warfarin 25 mg daily should alert any staff member to seek clarification. Any dose of a medication that requires a lot of tablets, capsules, vials, etc, should be a red flag that the dose may be too high.

Teaching can be a good way to help others as well as yourself stay on top of emerging information. It gives the presenter a chance to thoroughly review the current literature on a specific topic. Pharmacists and pharmacy technicians can present topics to coworkers, patients, prescribers, clinic or hospital staff, etc.

Good communication is one of the best ways to reduce medication errors [65]. Establish an open line of communication with all staff. Make sure any unclear instructions or prescriptions are clarified. Encourage open communication and be willing to accept and provide constructive input on how to improve your system to help decrease errors.

Intimidating behavior is not conducive to good communication. Regardless of your level of expertise, understand that anyone can and does make mistakes.

Pharmacists and other healthcare workers are not always trained in managerial skills, how to relate to people, or effective communication [66]. These are skills that can be learned and must be developed and practiced. Consider attending courses or classes on communication strategies. Set up in-services for your pharmacy's staff; you could even invite an expert to your next staff meeting to discuss effective communication.

Patients who are educated on their condition and treatment and who are actively involved in their own care can be a powerful tool to help prevent medication errors. Answering questions and addressing patient concerns comes quite naturally to most pharmacists and pharmacy technicians. But you should also encourage patients to ask questions and get involved in their medication therapy [67]. Also suggest that patients always check their own medications. For example, let patients know they should always ask about pills that don't look, taste, or smell the same as the last time they had a prescription filled, or if anything else looks out of place.

Patients should have the pharmacist double-check their medications if they have concerns. An easy way is to have the patient open their bag and verify their prescriptions. Some prescribers give patients a patient-guided counseling checklist with questions they can ask the pharmacist. The checklist covers questions related to dosing, side effects, interactions, drug administration, storage, alcohol use, etc. This is one way to increase patient participation. It might also reduce the chance for errors to slip by and can increase patient compliance. Plus, patient satisfaction can improve with this type of interaction. Patients want to feel like they're being listened to and getting their questions answered. For a great start to this approach, check out the "Know Your Medicines" program from Alberta Health Services for lists and tools to use with your patients [68].

Any pharmacist, pharmacy technician, or other pharmacy staff member can identify potential problems in the system. For example, performing product inventory provides pharmacy technicians the opportunity to identify similar-looking products that sit next to each other on the shelf. Similar-looking products can then be rearranged to differentiate one product from another. The best way to prevent medication errors is to design a system that includes adequate safety nets with checks and balances. When errors do slip through, documenting and evaluating the cause of the error will help improve the entire system.

At the organization level, it's important to establish a Just Culture that works to minimize the incentive and ability to act on at-risk behaviors. Providing technology that helps improve prescribing and dispensing accuracy is also key. In addition, medication reconciliation during transitions of care is a very important element that many organizations have implemented to help catch and prevent medication errors. To ensure overall success, a medication safety leader, ideally a pharmacist, should lead the medication safety efforts throughout the organization [6]. Pharmacists should also be involved in technology decisions to ensure the safety and effectiveness of technology that impacts the medication-use process [75].

As mentioned before, it's important that healthcare organizations establish a Just Culture that does not tolerate at-risk behaviors. Individual members of such organizations must be motivated and rewarded for using safe practices. Shortcuts and workarounds for the sake of efficiency or to circumvent system problems must be identified and replaced with behaviors and practices that keep patients safe.

E-prescribing

E-prescribing is the electronic sending and receiving of prescriptions. E-prescribing can give prescribers the ability to electronically send an accurate, error-free, and understandable Rx from the point of care (clinic, office, etc.) to a pharmacy. It virtually eliminates the problem of illegible handwriting and can help with other problems such as look-alike/sound-alike drug names. However, some evidence suggests that the overall rate of medication errors has remained the same with the increase in electronic prescribing [74]. Be alert to potential pitfalls that can lead to errors. In one study of five community pharmacies, the four most common errors observed in electronic prescriptions were inappropriate drug quantity (40%), wrong duration of therapy (21%), wrong dosing directions (19%), and wrong dosage formulation (11%) [76].

Even though e-prescribing reduces the risk of some errors, there are new types of errors e-prescribing can introduce. Workarounds can be particularly troublesome. For example, when the prescriber can't find the drug that they want to order in the system, they may type the drug name in the comments field. Users should always be very wary when they need to use a workaround. If something can't be entered into the prescription, there may be a valid reason. If you work in a hospital or clinic with prescribers, any prescribing "workarounds" you see occurring should be reported to your support person or team for assessment and potential correction.

Another type of error introduced by e-prescribing systems is selecting incorrect information from a drop-down menu. For example, "metoprolol tartrate" is just a click away from "metoprolol succinate," as are "teaspoon" from "tablet" or the number "1" from the number "10." Be vigilant for these types of deviations when you are filling e-prescriptions. Pharmacy technicians should alert the pharmacist if they see something that just doesn't add up, so that the pharmacist can clarify with the prescriber. If you notice a recurring error, collaborate with the prescriber's office to address this. They may be able to change a drop-down menu to eliminate an entry that is causing problems.

Collaboration between pharmacists, technicians, and prescribers is key to avoiding common errors with electronic prescriptions. Review patient profiles to pick up discrepancies, and always check for notes and comments that may be included in an e-prescription. For instance, if you see "1 tablet PO daily" in the sig of a warfarin e-Rx but miss the sig "One-half tablet on Mon, Wed, Fri" in the notes field, the patient will get the wrong dose. Contact the prescriber for any discrepancies or conflicting information. Clarify any "as directed" sigs with the patient or prescriber. Patient counseling should be used as a final check before a medication goes out. Share problems, near misses, and errors with your coworkers so everyone can be aware of pitfalls and help brainstorm solutions.

Computerized Physician Order Entry (CPOE)

Computerized physician order entry (CPOE) is a term usually used for "e-prescribing" within hospitals or clinics. Like electronic prescribing in the community, physician order entry in hospitals can reduce illegible writing, allow prescriptions to get to pharmacies quicker, and reduce errors with similar drug names. Facilities using CPOE have shown a reduction in overall error rates of 55%, and an 88% reduction in serious medication errors [71].

CPOE systems still require human intervention and checking. They shouldn't be seen as foolproof or elicit overconfidence. The current view is the same as with e-prescribing, while overall errors may go down with CPOE, new types or causes of errors will show up [72]. For example, mix-ups from illegible prescriptions may be replaced by prescribers clicking the wrong drug. And missing important drug interactions can still occur despite the availability of the information at the point of prescribing. This is because of alert fatigue caused by the sheer volume of these drug interaction alerts and other messages.

Barcode Scanning

Barcode scanning can dramatically reduce medication errors. Barcode scanning can be used to improve the accuracy of the medication use process in the pharmacy (e.g., stocking, compounding, dispensing) and on patient care units, prior to the administration of meds. Barcode scanning has been shown to reduce different types of medication errors by 36% to 96% [73].

If barcode scanning is used in your pharmacy, be sure to follow the guidelines established. Do not use workarounds. Report any issues with scans that don't work as expected. When multiple packages are being used or dispensed, always scan each individual package.

To help prevent errors that occur when patients transfer into, out of, or between healthcare facilities, community pharmacies, primary care providers, and hospitals must share information from patients' medication profiles. This is a part of medication reconciliation, and this sharing of information for a mutual patient is allowed under the U.S. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Medication reconciliation refers to the process of reconciling patients' medication lists at all points in the healthcare system to provide seamless care, and it's been on the list of The Joint Commission's National Patient Safety Goals for years. Over half of hospitalized patients who are transferred may have potential problems with their medication profiles. These discrepancies have the potential to cause errors during hospitalization as well as after discharge. Medication reconciliation can help reduce these medication omissions, duplications, dosing errors, and drug interactions [80]. Pharmacy teams should share accountability with other hospital and health-system leaders for the ongoing success of the medication reconciliation processes across the continuum of care [81].

According to a report from the World Health Organization, on admission to the hospital, at least one medication discrepancy was reported in 3% to 97% of adult patients and 22% to 72% of pediatric patients; 62% of patients had at least one unintentional medication discrepancy during internal hospital transfer; and 25% to 80% of patients had at least one discrepancy or failure to communicate in-hospital medication changes at discharge [82]. In addition, over 60% of patients may have errors due to incomplete patient medication histories [83]. There are many reasons why medication histories aren't accurately taken. For example, the patient may be too ill or may have incomplete knowledge of their medications. Involving prescribers, family members, and community pharmacies can help with obtaining accurate and complete medication histories. However, collecting accurate histories takes time [84]. Typical problems found when obtaining medication histories include patients taking a medication not on their history or a different dose than provided by the history, or not taking a medication that they should be taking. For medication reconciliation, it's important to make note of any intentional discrepancies between the meds a patient was taking prior to admission and the meds they receive as an inpatient. For example, if a medication the patient was taking at home was not started in the hospital due to a formulary switch, it's important to document this reason. This way, the patient can be restarted on the medication they were on prior to admission once they are discharged.

Inaccuracies don't just occur with hospital admissions. It has been found that up to 76% of patients' discharge summaries may include errors [76]. These types of medication errors can be reduced by 70% when pharmacists evaluate medications at admission, transfer, and discharge [83]. Pharmacists can be alert for patients who are at high risk or on complex medication regimens for follow-up by their local pharmacist [6]. On discharge, watch for medications that may be duplicates in therapy. As previously mentioned, patients may have been switched from a home medication to a formulary medication on admission. An error can occur if upon discharge, a prescription is given for both the original home med plus the hospital med. For example, a hospital may stock only one proton pump inhibitor (PPI; e.g., lansoprazole, pantoprazole). If a patient takes lansoprazole at home, they may be switched to pantoprazole on admission if that is the formulary PPI. In this example, it's important to make sure that this patient does not get prescriptions for both lansoprazole and pantoprazole on discharge. Any aspect of medication use that is unclear, confusing, or contradictory should be addressed and information uncovered until the issue is resolved.

One of the greatest fears of any pharmacist or pharmacy technician is to be involved in an error that harms a patient. Despite the best and most conscientious efforts, medication errors still slip through.

The first step in dealing with a medication error is to take care of the patient [86]. This is the right thing to do. Get the details of the situation by asking the patient important questions, such as why they think an error occurred, whether the medication was taken, how much of the medication was taken, and how they are feeling. Pharmacists should contact the patient's other providers to explain the situation and discuss the best course of action. Pharmacists should try to speak with each provider directly, providing patient details or status, facts about the situation, and what has been done so far.

It's important to have a written protocol that describes procedures to follow in the event of a medication error [78]. Pharmacists and pharmacy technicians should become familiar with these procedures. Knowing how to proceed when a medication error occurs is important for handling the situation properly. When a medication error occurs, you need to act quickly and professionally.

It's also important to understand the effect that medication errors have on the people involved. Patients will experience a set of emotions, such as being scared, confused, anxious, or angry. Pharmacists and pharmacy technicians are extremely concerned when a medication error occurs. There are feelings of fear, panic, guilt, and remorse. This is why the staff involved with the error is sometimes referred to as the "second victim." These feelings can adversely affect the manner in which the pharmacist or pharmacy technician reacts to the situation. Experts acknowledge that learning how to take care of the healthcare workers involved in a medication error is an important part of the process [79].

If a patient reports a medication error to a pharmacy technician, the pharmacist should be made aware right away. Let the pharmacist take over from here.

Here are some suggestions for pharmacists to help approach this difficult experience [84,89]:

Handling the initial patient interaction