Course Case Studies

- Back to Course Home

- Participation Instructions

- Review the course material online or in print.

- Complete the course evaluation.

- Review your Transcript to view and print your Certificate of Completion. Your date of completion will be the date (Pacific Time) the course was electronically submitted for credit, with no exceptions. Partial credit is not available.

Patient A, a woman 20 years of age, arrives at her primary care clinician's office with red eyes, profuse epiphora, and edematous eyelids. She noticed redness and tearing in her left eye three days ago. These symptoms develop in her right eye the next day, so she calls in sick to her gymnastics teaching job at a local youth center. She notes no blurred vision, photophobia, halos, or pain/burning sensations, but she feels like "sand is in my left eye." She also has a slight headache, sneezing, and a runny nose. Patient A initially assumed her condition was caused by allergies and self-medicated (unsuccessfully) with an over-the-counter antihistamine and ibuprofen. She is unsure if any of the children at the youth center have similar symptoms. Based on the symptoms and history, the clinician suspects adenoviral conjunctivitis and prepares to examine Patient A.

Rationale and comments: When diagnosing a red eye, the primary care clinician should first determine if a referral to an ophthalmologist is necessary to protect the patient's vision. Serious conditions associated with a red eye (e.g., scleritis, uveitis, angle-closure glaucoma, keratitis) typically affect vision and/or cause severe pain, which Patient A does not have. Although conjunctivitis is primarily diagnosed on the basis of the patient's history and symptoms, further evaluation is necessary for confirmation and to ensure no other eye conditions are occurring simultaneously.

Assessment and evaluation: Physical examination shows that Patient A's pupils are normal, and no ciliary flush is detected when evaluated in natural light. The perilimbal region is clear. The only additional feature observed during her ocular evaluation is preauricular adenopathy. With use of a rapid immunochromatography test, adenoviral antigen is found in tear fluid obtained from Patient A's left eye.

Rationale and comments: The rapid immunochromatography test detects adenoviral antigen in human eye fluid. This point-of-care test, which shows results within 10 minutes, has been found to be as effective as polymerase chain reaction or cell culture. Ciliary flush and pupillary abnormalities are not characteristic of conjunctivitis but are indicative of red-eye conditions such as iritis, angle-closure glaucoma, or keratitis. These features should be assessed during the examination of a red eye. Little or no injection around the iris is indicative of conjunctivitis. Preauricular adenopathy is characteristic of viral conjunctivitis.

Ongoing management: Patient A is informed of the diagnosis of adenoviral conjunctivitis and is told that the condition is self-limiting and will likely resolve itself in 10 to 14 days. Antibiotics are not offered to her, and she is told that applying cool compresses for 10 to 15 minutes may provide some relief. The clinician also tells Patient A that she likely contracted this highly contagious condition from one of the children at the youth center and that she should not return to work until she is symptom free (likely 5 to 10 more days). To promote resolution as well as to prevent reinfection and spread of adenoviral conjunctivitis, Patient A should practice very strict hygiene—especially frequent hand washing; avoidance of sharing towels/soap, pillowcases, and keyboards; and washing of sheets, towels, and other items that may spread the infection. She is advised to avoid touching her eyes, and is given an appointment for a check-up in seven days.

If possible, the youth center should be contacted to inform individuals working at or attending the center that they should refrain from coming to the center if they have conjunctival symptoms. Additionally, the use of good hygiene should be stressed to the children and staff to avoid acquiring conjunctivitis.

Rationale and comments: Patient A is not offered antibiotics because there is no evidence of bacterial involvement and antibiotics will not be effective against the viral infection.

The incidence of adenoviral conjunctivitis peaks during the summer months. Individuals exposed to child-oriented facilities are at the highest risk, perhaps because the spread of the condition is fostered by the concentration of children in combination with their lack of appropriate hygiene.

Follow-up management: At the seven-day visit, Patient A's eyes appear free of redness, tearing, discharge, and are no longer itchy. She is not referred to an ophthalmologist.

Rationale and comments: Primary care clinicians can treat most individuals with conjunctivitis without referral. Patient A would require referral to an ophthalmologist if her condition was unchanged or worsened or if regions other than the conjunctiva were affected.

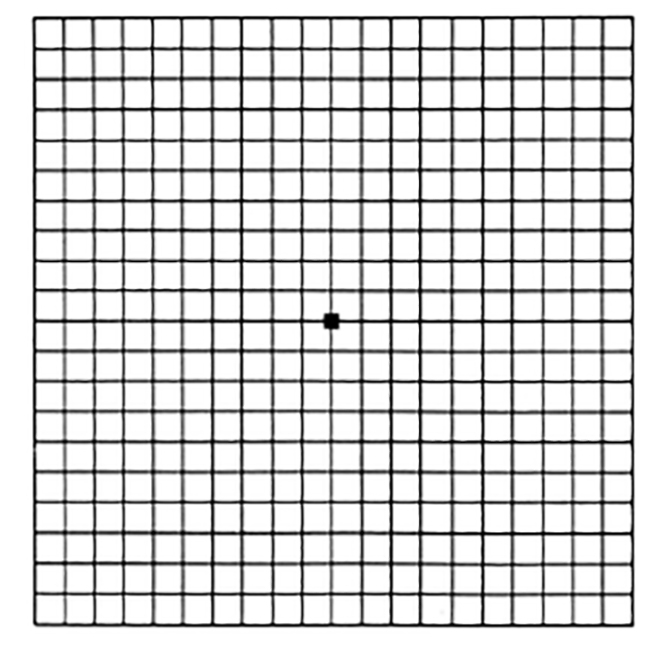

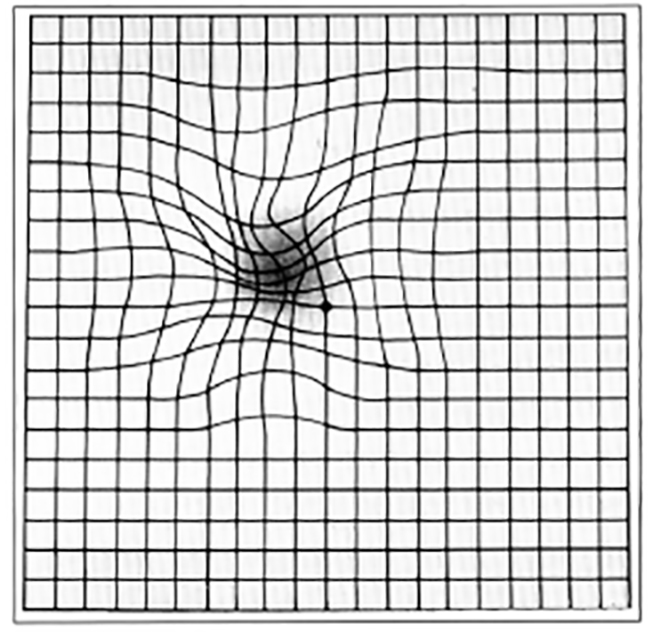

Patient C, an active White man 83 years of age, was diagnosed with non-neovascular (dry) age-related macular degeneration at 77 years of age. Patient C attempted to quit smoking cigarettes nine years ago, and although he smokes much less, he still smokes periodically. The ophthalmologist gave Patient C an Amsler grid to self-monitor his vision. Last year, some centralized gridlines appeared distorted to the patient, and the ophthalmologist determined that age-related macular degeneration had progressed significantly (Figure 2 and Figure 3). (Patient C had drusen of about 100 micrometers bilaterally.) While at his primary care clinician's office for a check-up, Patient C tells the clinician that some lines on the grid appear to be missing and he can no longer read his watch. He states that his next age-related macular degeneration-related visit with the ophthalmologist is five months away.

Rationale and comments: Patient C's dry age-related macular degeneration was diagnosed in an early stage. The Amsler grid was given to help determine when the disease progressed to the intermediate stage, when a combination of antioxidant vitamins might be effective in slowing progression.

Assessment and evaluation: After completing Patient C's check-up, the clinician refers him to his ophthalmologist for an appointment earlier than the one scheduled. The physician reminds Patient C that age-related macular degeneration will not take his sight away completely; it will affect only his central vision, and his peripheral vision will remain intact. A smoking cessation program is recommended. Patient C is also asked about his ability to perform everyday functions and what activities he enjoys. He notes that his children take care of the utility and other bills with an electronic payment online. A few months ago, his wife forbade him from driving anymore. But he enjoys cooking meals for his wife a few times a week, solving crossword puzzles, reading the newspaper daily, looking at pictures of his great grandchildren, and watching sports on television. To prime him for a discussion with his ophthalmologist, the clinician briefly tells him about low-vision devices that may be of benefit to him, such as magnifiers, closed-caption television, high-contrast watch faces, and a computer that reads printed material. The physician also tells Patient C that the ophthalmologist may prescribe treatment with a combination of antioxidants (vitamin C vitamin E, beta carotene, zinc oxide, and cupric oxide). The physician explains, however, that Patient C should not take beta carotene supplementation because he continues to smoke.

Rationale and comments: A large trial has shown that the combination of vitamins C and E, zinc, copper, and beta carotene slows central vision loss in individuals with intermediate dry age-related macular degeneration. However, beta carotene should be removed from this supplement regimen for patients who smoke. Additionally, other large studies have shown that beta carotene may accelerate progression of age-related macular degeneration. Patient C should be encouraged to quit smoking, as smoking accelerates the progression of age-related macular degeneration.

Ongoing management: Patient C's primary care clinician continues to monitor quality of life associated with his vision loss for two years. The age-related macular degeneration evolved into the neovascular (wet) form, and he is being treated by his ophthalmologist accordingly. Patient C, now 86 years of age, is no longer able to cook and has difficulties with other activities. His wife, who is 76 years of age, tells the clinician that she fears he may fall at home because his favorite area in the house has stairs. The clinician has also noticed that Patient C exhibits signs of depression. At each appointment, the clinician has discussed information about government and private agencies that can help with redesigning the home for Patient C's needs, low-vision rehabilitation programs, support and activity groups, and psychotherapy. The clinician has also asked questions to determine the patient's psychosocial status. The physician prescribes an antidepressant for Patient C.

Rationale and comments: A devastating consequence of age-related macular degeneration-induced central vision loss is the accompanying loss of independence. As vision declines, an individual with age-related macular degeneration and his or her family find that tasks such as cooking or navigating the home are dangerous. Studies suggest that loss of visual acuity correlate to increased injuries and falls. Individuals' dissatisfaction with the inability to perform valued activities increases the risk of depression.

Follow-up management: Patient C's primary care clinician continues to monitor his functional and quality-of-life needs. Although his central vision has declined, Patient C is satisfied with the support he has from his family and others and his functioning with low-vision devices. An occupational therapist certified in low-vision rehabilitation has helped the patient and his wife make small modifications to their home to increase his independence. Patient C is happy that he can enjoy cooking occasionally again.

Rationale and comments: At each visit, Patient C's primary care clinician provided education to the patient and his family about services to help him adapt to his vision impairment. This information played a major role in protecting the patient's quality of life and independence. The low-vision rehabilitation program and services helped the patient's family become involved in preparing the couple for age-related macular degeneration-associated life changes. For instance, because the couple's health was generally good and they wished to stay in their home as long as possible, their children completed a series of practical home modifications to help with Patient C's low-vision problem through a state-funded program. To reduce the caregiving burden, a caretaker was hired to perform weekly light cleaning and to precook nutritional meals. Low-vision devices were purchased as needed. Also, Patient C and his wife continue to attend weekly support group sessions hosted by their local hospital.

- Back to Course Home

- Participation Instructions

- Review the course material online or in print.

- Complete the course evaluation.

- Review your Transcript to view and print your Certificate of Completion. Your date of completion will be the date (Pacific Time) the course was electronically submitted for credit, with no exceptions. Partial credit is not available.